| When to See Hawks | Where to See Hawks | How to See Hawks |

| Annotated List | Other Species | Glossary |

Fall Hawkwatching Guide

By Ron Pittaway

Published in OFO News 17(3):1–8. 1999. Please Ron if you have questions.

OverviewTop

In response to the annual shooting of migrating birds of prey, the study of hawk migration began in September 1934 when the legendary Maurice Broun first climbed the newly established Hawk Mountain Sanctuary in Pennsylvania. Interest in hawkwatching has grown rapidly in recent years and has spread worldwide. Hawks are magnificent to watch, especially in flight, as they stream by Ontario’s top watches. There are 23 species of diurnal raptors on the Ontario checklist. This guide treats the fall migration period of vultures, Ospreys, hawks, kites, falcons and eagles in southern Ontario, including directions to the best hawkwatches.

When to See HawksTop

The following chronology applies to watches along Lakes Ontario and Erie. See Table 1. Fall migration begins slowly in mid‐August with most species peaking in September and October; the migration ends gradually after mid‐November into December. In late August, Ospreys, Northern Harriers, Sharp‐shinned Hawks, Broad‐winged Hawks, Merlins and American Kestrels begin migration with bigger movements of these species in September. Most Broad‐winged Hawks surge south in spectacular numbers within the space of a week on a few lucky days in mid‐September. A few Bald Eagles are regular throughout the whole migration period. After mid‐September increasing numbers of Turkey Vultures, Cooper’s Hawks and Red‐tailed Hawks join the flow. Tundra Peregrine Falcons peak in late September and early October. Cooper’s Hawks peak in early to mid‐October. Red‐shouldered Hawks peak from the middle to late October. Red‐tailed Hawks peak in late October and early November. Rough‐legged Hawks, Northern Goshawks and Golden Eagles are regular in small numbers from mid‐October to early November. There is the occasional good flight after mid‐November, but numbers are usually much lower. Some raptors continue to migrate into December. Note: Keep in mind that most of the above raptors also winter in southern Ontario.

Weather: The best viewing conditions for fall flights occur during cold fronts with northwesterly and north winds. Cold fronts trigger migration and the associated northwesterly winds cause hawks to pile up and fly lower along the north shorelines of the Great Lakes. Indicators of an upcoming flight are: (1) the recent passage of a low pressure system (hawks are held up by bad weather), (2) a rapidly rising barometer indicating an approaching high pressure system, (3) decreasing temperature and humidity, (4) northwest and north winds. Note: Hawks migrate during most weather conditions except heavy rain, but are often missed because they fly higher on a broad front in warm weather away from shorelines. The strategy used by most migrating hawks is to glide from thermal to thermal. Wind direction also affects where the migration path will be on a given day. Hawks fly along shorelines in calm conditions and light winds from most directions. but strong onshore winds keep the birds well inland. Some hawkwatchers monitor the marine weather forecasts on Channel A of Environment Canada, which gives continuous updates of wind speed and direction. Inexpensive weather radios are available.

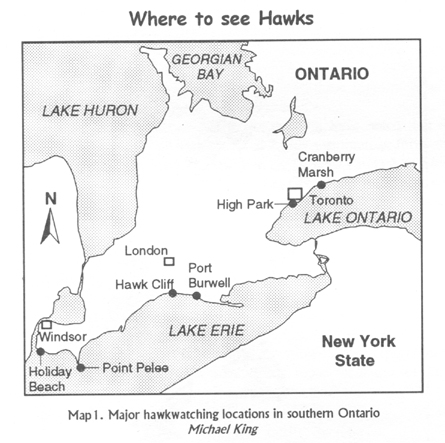

Where to see HawksTop

Southern Ontario has some of the finest fall hawkwatching sites in North America. A glance at Map I shows the funneling effect of southwestern Ontario between Lakes Huron, Ontario and Erie. Most migrating hawks exit the province across the Detroit River south of Windsor. The best sites are located along the shorelines of the Great Lakes because most hawks are reluctant to flyover the Great Lakes. When hawks migrating south on a broad front encounter the north shores, they parallel the shorelines until they can turn south again. Most hawks move west along Lakes Ontario and Erie. North and northwest winds help concentrate the flight lines in a narrow corridor close to the lakes. Flights are smaller going east from Cranberry Marsh along Lake Ontario, except at Prince Edward Point at the east end of the lake, where flights are associated with strong north‐westerly winds. Hawks going around the west end of Lake Ontario move southwest and appear to reach Lake Erie just east of Port Burwell. Farther east, such as at Long Point, not many hawks are seen. Hawk numbers increase going west along Lake Erie from Port Burwell to Holiday Beach. See Map 1 for relative positions of the major fall hawkwatching sites in southern Ontario. Directions to these site locations are given below.

Cranberry Marsh: Situated in Lynde Shores Conservation Area in Whitby about 40 km east of Toronto. From Toronto exit Highway 401 at Salem Road, go right (south) about one km to Bayly Road, turn left (east) and go about 3 km to just past Lakeridge Road. Take Halls Road (dirt) on the right, go 1. 6 km and park on roadside. Walk east on a narrow trail about 100 metres to the south platform overlooking Cranberry Marsh. From the east, exit 401 at Brock Street in Whitby, go south (left) 0.5 km to Victoria, then go west (right) 3.3 km to Halls Road on your left just past the main entrance to Lynde Shores Conservation Area.

High Park: This fabulous site in Toronto’s famed High Park is in the city’s west end between the Gardiner Expressway and Bloor Street. Go to parking lot of Grenadier Restaurant from Bloor Street via West Road or take the east entrance off Parkside. Note: On Sundays and holidays from I May to 1 October, vehicle entrance to High Park is from Bloor only. Hawks are viewed from the small knoll known as Hawk Hill just to the north of the restaurant. High Park offers excellent birding throughout the year. See Bob Yukich’s (1995) site guide to Toronto’s High Park in OFO News 13(3):2‐3.

Rosetta McClain Gardens Raptor Watch: Situated on the Scarborough Bluffs in east Toronto. Directions: Going east from Birchmount Road on Kingston Road, turn right at first traffic light into the parking lot. Walk a short distance to the edge of the bluff overlooking Lake Ontario.

Port Burwell: Located on Lake Erie midway between Port Stanley (Hawk Cli:fl) and Long Point. This new site has comparable numbers to Hawk Cliff. From Highway 401, exit south at Ingersoll to Tillsonburg on Highway 19 and proceed to Port Burwell Provincial Park. There is a small fee to enter. Go to the westernmost parking lot of the day use area, which has a great view to the north and east. Another spot is the flats along both sides of the mouth of Otter Creek with lots of parking and open views to the west, north and east. See Martin (1998).

Hawk Cliff: Located just east of Port Stanley on the shore of Lake Erie. Go south from St. Thomas on Fairview Avenue, which becomes County Road 22, until you reach the lake. Hawk Cliff was once the most famous hawkwatching site in Canada. In recent years, access has been restricted and a row of fast growing trees has made viewing difficult. It is recommended that you now use Port Burwell with its excellent public access. See Martin (1998) for background information on Hawk Cliff and Port Burwell. To find your own hawkwatch site along Lake Erie, Dave Martin says to look for the following features: (1) A road that dead ends at the lakeshore, (2) a clear view from the southeast to the northeast, (3) one where you can see the cliff edge because Ospreys, falcons and harriers like to catch the updrafts, and (4) one with nearby woods because accipiters like to follow a wooded corridor.

Point Pelee: The best spots are the Tip, parking lot at the Visitor Centre and Delaurier Trail parking lot. Sharp‐shinned Hawks are common in September, keeping most small land birds well hidden! You will get fabulous views of Peregrines in late September and early October. Golden Eagles are regular from mid‐October to early November. See Tom Hince’s (1999) A Guide to Point Pelee and surrounding region, published by the author and available in the park. There is a fee to enter Point Pelee National Park.

Holiday Beach: Holiday Beach Conservation Area is located between Pelee and Windsor near Maiden Centre on Essex County Road 50. There is a small fee to enter. Follow the signs to the viewing tower. Huge flights of Broadwings occur in mid‐September. Holiday Beach tallies the highest hawk numbers in Canada. See the excellent guide by Chartier and Stimac (1993).

Lake Huron: Good flights have been seen along shores of Lake Huron at Pinery Provincial Park and Sarnia during east winds. Moderate hawk flights have been reported along the east shore of Georgian Bay associated with northeast winds (Morrison 1995). Good flights of Sharp‐shinned Hawks in September, associated with northwesterly winds, have been observed at Great Duck Island 15 km south of Manitoulin Island in Lake Huron. Most of these Sharpies, after flying southeast over open water, returned to Manitoulin Island, possibly “island‐hopping” to the Bruce Peninsula. Another hawk flight moves northwest at Mississagi Light at the western end of Manitoulin, probably "island‐hopping" into Michigan. New sites wait to be discovered.

Lake Superior: On the north shore of Lake Superior there are several hawk lookouts and some yet to be discovered in this vast wild area: (1) Craig’s Bluff near Marathon is good in September and the second half of October brings Rough‐legged Hawks and a few Golden Eagles. Walk east from Marathon along the railway tracks about 3 km or 45 minutes to a large sand bluff. Climb to the top of the bluff for a good view of Lake Superior. (2) Thunder Cape is good for Sharp‐shinned Hawks in September and Rough‐legged Hawks in October and November with a mix of other species in smaller numbers. Thunder Cape Bird Observatory is a 13 km hike from Silver Islet down the Lake Superior shore. South of Thunder Bay, the Ontario shoreline of Lake Superior is too irregular and indented to produce a good funnelling effect. In fact, big flights usually are not encountered until you reach Hawk Ridge in Duluth, Minnesota.

How to See HawksTop

The following contains information on seeing and enjoying the hawk migration. See also definitions in the Glossary and recommended reading in the Literature Cited.

Aging Eagles: Bald Eagles take five or more years to reach adult (definitive) plumage. Golden Eagles probably require four years. Very few hawkwatchers really know how to precisely age eagles. Many of the ages assigned to predefinitive (immature) eagles are pure guesswork, especially distant birds. Keep in mind that adults and juveniles (first year) form the bulk of the population. Second year, third year and fourth year birds are increasingly rare in the population.

Hawk ID: Identifying hawks correctly takes considerable practice. Experienced birders use a combination of “jizz” (general impression of size and shape) and field marks. Most distant jizz identifications of common hawks by experienced observers are highly reliable. However, the ID of rare and out of season species should not be based solely on jizz. Make sure that you see field marks that are 100% diagnostic. First, group raptors into accipiters, buteos, falcons, harrier, Osprey, kites, eagles and vultures. Second, keep in mind that hawks often change their shapes depending upon the type of flight: soaring, gliding, flapping and sailing, power flight in pursuit of prey and so on. Almost all raptors can appear like another species depending on flight style and size illusions. Accipiters and falcons in a full soar can look like buteos; accipiters in power flight look like falcons and so forth. Concentrate on proportions, body size, wing and tail length, wing width versus tail length, amount of flapping, fast or slow flapping, tight or wide soaring circles and so on. Hawks are easier to spot against clouds than clear skies. However, the same hawk will appear more washed out against clouds versus a bright blue sky. Tip: To learn what hawks look like at a distance, practice following close birds of known identity to the limits of sight.

Hawk Time: Hawk watchers record hourly totals of each hawk observed using Eastern Standard Time, even when Eastern Daylight Time is in force.

Healthy Eyes and Skin: Watching hawks exposes your eyes and skin to damaging sunlight. Cover up and wear a wide hat and sunscreen. To protect your eyes wear sunglasses or prescription glasses with ultraviolet protection.

Hybrids and Exotics: Hawk hybrids in nature are almost unknown. However, falconers keep exotic species and hybrids. This list includes hybrid Cooper’s x Harris’s Hawk, Merlin x Gyrfalcon, Saker Falcon (Gyrfalcon‐like), Ferruginous Hawk, European American Kestrel and so on. When these birds escape, they are likely to be misidentified and/or considered a wild birds.

Juveniles First: In most hawk species, the juveniles migrate earlier in the fall than the adults, with some exceptions being the Osprey, Peregrine Falcon and probably the Golden Eagle. Juvenile hawks in fall are migrating for the first time. Juveniles may fly lower than adults because they are not as skilled at using thermals.

Lawn Chair: An essential comfort item along with a lunch and thermos of coffee.

Male or Female: In most diurnal raptors, but not all, the sexes are similar in coloration. In all species, however, the females are larger than the males, but only in a few species such as the accipiters can extremes be reliably sexed by size in the field.

Noonday Lulls: There is often a noticeable lull in numbers at midday at many watches. Most hawks are probably just too high to see in the bright sky and heat of midday.

Ozone Bird: A high bird barely visible even with binoculars! Also known as a bird in the stratosphere. The altitude of migrating hawks generally increases from morning to afternoon. Many hawks migrate above the visible range.

Plumages: Hawks come in two main plumages: juvenile and adult. In most species, the juvenal plumage is retained about a year before the prolonged molt to adult plumage during the summer of its second calendar year. Adults also molt during the summer. Some species interrupt (stop) their molt before migration and finish it on the winter grounds. Aging hawks is easy in fall. Most birds are clearly either juvenile or adult.

Population Changes: It is important to keep in mind that most raptors have good and bad breeding years depending on weather and prey cycles. The ratio of juveniles to adults of each species seen at hawk watches often gives a measure of breeding success. Weather is the single biggest factor affecting total hawk numbers seen from year to year. Like Snowy Owls, Rough‐legged Hawk numbers fluctuate because of lemming cycles in the Arctic. Northern Goshawks breeding in the boreal forest irrupt southward in numbers about every 10 years when there are declines in Ruffed Grouse and Snowshoe Hares. Some species, such as the Osprey, Bald Eagle and Peregrine Falcon, are increasing since the banning of DDT. Mainly because of different weather patterns affecting flight lines and how high hawks fly, expect to see wide yearly fluctuations in hawk numbers. The importance of long term counts, including the ratios of juveniles to adults, is that population trends become evident, particularly when correlated with other watches.

Reference Points: At each hawkwatch, there are reference points that spotters use to tell others where to look for hawks. These include silos, towers, trees and cloud formations. Also every hawkwatch has its own particular flight lines with certain species consistently appearing in the same part of the sky. Observers often use the clock method to point out the location of a hawk, for example, referring to the sky as 12 o’clock for midway between the two horizons, thus 10 0’ clock, 2 0’ clock and so on.

Scanning Tip: Experts usually spot the hawks first. Why? They scan with their binoculars the usual flight lines and the bases of cumulus clouds where kettles often form.

Telescopes: Many top hawkwatchers use a telescope. A scope on a sturdy tripod is essential for distant birds. Make sure your tripod has a fluid head for easy panning. A 22x wide angle or a zoom 20‐60x lens is ideal; higher fixed powers such as 40x and 60x make it difficult to locate birds in a cloudless sky!

Annotated ListTop

Black Vulture: (BV) Very rare. Black Vultures are increasing and spreading north. For ID and status in Ontario, see Duncan (1990).

Turkey Vulture: (TV) Common to abundant. The Turkey Vulture continues to increase and spread north as a breeder. Holiday Beach recorded a yearly average of 8246 from 1973 to 1985 whereas the 1986‐1995 average increased to 13523. The Turkey Vulture will soon pass the Sharp‐shinned Hawk as the second most common raptor at southern Ontario hawkwatches. Peak flights come in October. TVs often fly in lines like squadrons of enemy bombers. They also form large kettles. They occasionally flap with deep wingbeats. TVs are almost the size of an eagle; they are best told from eagles by their tiny head, strong V dihedral and usually rocking flight. For ID and status in Ontario, see Duncan (1990).

Osprey: (OS) Uncommon migrant. Numbers have increased rapidly since the banning of DDT in the early 1970s. For example, there were about five pairs nesting in the Kawartha Lakes north of Lake Ontario in 1975 versus more than 100 pairs in 1999. The increase was assisted by the erection of nesting platforms and the Osprey’s greater use of hydro poles for nesting. Adult Ospreys start wandering southwards in mid‐August. A record 29 Ospreys passed Cranberry Marsh on 28 August 1999. Numbers usually peak in mid‐September with a rapid drop off in early October and virtually none later.

Swallow‐tailed Kite: (ST) Casual. A very early fall migrant so this species is extremely unlikely to be seen in Ontario after early September.

Mississippi Kite: (MK) Very rare. Slowly expanding range northwards. This very early fall migrant is extremely unlikely to occur in Ontario after early September. Watch for it on days of big dragonfly movements.

Bald Eagle: (BE) Rare. Another success story, the Bald Eagle is increasing nicely since the banning of DDT. Numbers often peak in September, but scattered individuals are seen over the entire migration period. Bald Eagles soar and glide on horizontal wings for long periods without flapping. Flap is slow and heavy. Head projects out more than half the tail length. Trailing edge of wings is straight. Goldens usually soar and glide with a slight dihedral, appearing like a huge buteo with their smaller head. Trailing edge of wings on Goldens shows a bulge in the secondaries and narrowing at the base of the wings. Caution: Juvenile Balds are often confused with adult Goldens. It is better to put “unidentified eagle” on your list if there is any uncertainty. For ID and status in Ontario, see Duncan (1990).

Northern Harrier: (NH) Fairly common from late August to November. Juvenile numbers peak in mid‐September. Late season birds are mostly adult males. Migrating harriers often fly very high, presenting an ID challenge to those used to seeing them flying low.

Sharp‐shinned Hawk: (SS) Common to abundant. After the Broad‐winged Hawk, the Sharpie is usually the second most common hawk at watches in Ontario. Juveniles predominate through September with increasing numbers of adults in October. At southern Ontario hawkwatches, the ratio of Sharp‐shinned to Cooper’s ranges from about 40: I to 20: I. Compared to Cooper’s, many Sharpies can be identified at a distance by the combination of their smaller heads, more rapid and fluttery wingbeats followed by shorter glides. Migrating Sharpies are often seen in early morning with a bulge in their crop, indicating that they have just eaten. Most hawks feed on migration. For accipiter ID in Ontario, see Duncan (1983).

Cooper’s Hawk: (CH) Uncommon to fairly common migrant. Numbers are increasing slowly following the ban on DDT in the early 1970s. Cooper’s peak in October, somewhat later than Sharpies. There are more debates about whether a bird is a Cooper’s or a Sharp‐shinned than between any other two similar species. In the past, some small male Cooper’s were counted as Sharp‐shinned Hawks. Compared to Sharp‐shinned, a typical Cooper’s has a bigger and longer head projecting farther ahead of straighter forward edges of the wings, the wingbeats are slower and glides longer, the tail is longer and distinctly rounded with a wider white tip. Cooper’s jizz is like a “flying cross”. For accipiter ID in Ontario, see Duncan (1983). For ID of juvenile Cooper’s, see Duncan (1987).

Northern Goshawk: (NG) Rare migrant in very small numbers. Slowly increasing as a breeder in the south. Most goshawks arrive after mid‐October usually peaking late October to early November. Big flights come about once in 10 years; however, the large numbers seen at Hawk Ridge (Duluth, Minnesota) are not seen in southern Ontario. Holiday Beach’s record day was 28 on 10 November 1991. Juveniles usually predominate. Small juvenile male goshawks are sometimes very difficult to separate from big female Cooper’s at a distance. Unlike most other hawks, the goshawk has a recognizable first basic (second year) plumage. First basic birds are like adults but browner above and more coarsely barred below; some are identifiable at close range. For accipiter ID in Ontario, see Duncan (1983). For ID of juvenile Northern Goshawk, see Duncan (1987).

Red-shouldered Hawk: (RS) Uncommon to fairly common migrant. Most Red‐shouldered Hawks migrate in October well after the Broadwings have gone. They peak the second half of October. A distant Red‐shouldered flapping and gliding with its tail folded can appear amazingly like a goshawk, but the latter has a longer tail and lacks the narrow translucent windows near the wingtips. Caution: Most juvenile buteos show wing windows, but they are squarer or more rectangular than on the Red‐shouldered Hawk. For ID of juvenile Red‐shouldered, see Duncan (1987). Note: Until the 1960s, the Red‐shouldered Hawk nested commonly in southern Ontario. It gradually disappeared as woodlots were heavily thinned for larger trees. This allowed the Red‐tailed Hawk, which prefers more open habitats, to displace the Red-shouldered Hawk from hundreds of small woodlots. Today the stronghold of breeding Red‐shouldered Hawk in Ontario is the heavily forested (poor Redtail habitat) southern part of the Canadian Shield north to Parry Sound, Muskoka, Haliburton County and Renfrew County south on the Shield to Kingston. Numbers appear to be relatively stable in recent years. For more information on status and management, see Iron (1995).

Broad‐winged Hawk: (BW) Common to abundant migrant. A few juvenile Broadwings begin drifting south in late August. Unlike other Ontario hawks, most Broadwings migrate through southern Ontario in about a week period in mid‐September, usually during one to three big surges. Big flights have a mixture of juveniles and adults. One day high counts in the thousands are seen along Lake Ontario and in the tens of thousands along Lake Erie. For example, High Park in Toronto recorded an early high of 4477 Broadwings on 8 September 1998. Holiday Beach on Lake Erie recorded a record 95499 Broadwings on 15 September 1984. When you are watching a kettle, the hawks will at some point stream off to the next kettle. Studies indicate that Broadwings migrate close to Lake Ontario on northerly winds and more inland on southerly winds. It is a sad time when the big Broadwing flights have passed for another year. A few BWs are seen into October, but most November reports are likely misidentifications. Dark morphs are exceedingly rare; be cautious of backlit birds that appear dark below. For ID of juvenile Broad‐winged, see Duncan (1987).

Swainson’s Hawk: (SW) Very rare migrant in southern Ontario with records ranging from 5 September to 22 October. Best time to look for Swainson’s Hawk is mid‐September to mid‐October. Swainson’s appears like a cross between a Red‐tail and a harrier. Watch for it with Broadwings and Turkey Vultures, but one could be with any group of hawks or by itself. Most are light morph individuals. Both juveniles and adults occur. Caution: High flying juvenile and female Northern Harriers can look like a Swainson’s. See Duncan (1986) on the occurrence and identification of Swainson’s Hawk in Ontario.

Red-tailed Hawk: (RT) The Redtail is the most common big hawk breeding in Ontario. Its migration peaks mid-October to early November. Redtails come in a variety of subspecies and morphs. Eastern Redtails occur in two common forms. Southern Redtails breeding in southern Ontario are white below with lightly marked belly bands and lightly streaked to unmarked throats. Northern Redtails (abieticola) are more buffy below with heavily streaked belly bands and darker streaked throats. Most Southern and Northern Redtails are easily separated in the field with practice. dark morph birds are very rare in Ontario; it is questionable whether they are Western Redtails (calurus) or very dark Northern Redtails. Harlan’s Red‐tails are even rarer than other dark Redtails. A few pale Krider’s Redtails are seen most years. Albinism is frequent in Red‐tailed Hawks, although full albinos are exceptionally rare. See Pittaway (1993) for status and identification of Red‐tailed Hawk subspecies and morphs.

Ferruginous Hawk: (FH) Casual. Before claiming a Ferruginous Hawk, be absolutely certain that you have ruled out Krider’s Red‐tailed Hawk and Rough‐legged Hawk. Most correctly identified birds reported in Ontario are probably released or escaped birds. Dark morph birds (no Ontario records) are much rarer than light morph birds.

Rough‐legged Hawk: (RL) Uncommon. Rarely seen before mid‐October, peaking late October to early November. Roughleg numbers vary from year to year, probably related to lemming numbers on their arctic breeding grounds. Most birds seen are light morph juveniles with their big dark belly bands. Dark morphs comprise about 20% of the migrants in most years.

Golden Eagle: (GE) Rare. Best time to see Golden Eagles is late October and early November. Holiday Beach’s record day of 24 was on 10 November 1991. Caution: All dark juvenile Bald Eagles and distant Turkey Vultures are often called adult Golden Eagles by inexperienced observers. Beware of Goldens reported before mid‐October! Watch for Goldens with flights of Red‐tailed Hawks and Turkey Vultures. Goldens often fly with a very slight dihedral, but they are bigger headed and do not rock from side to side like a Turkey Vulture. Very few Golden Eagles breed in Ontario; most migrants seen in southern Ontario probably breed in northern Quebec and Labrador. A Golden Eagle was tracked by satellite from its nest near Hudson Bay in Quebec. It crossed the mouth of James Bay into Ontario and apparently crossed Lake Ontario into New York State on its journey south. Two Goldens banded at Hawk Cliff were recovered in New Brunswick. Another success story, Golden Eagles have been increasing slowly in recent years. In the past, Golden Eagles were poisoned by eating strychnine baits used to kill wolves and coyotes. Poison is now banned to kill wildlife in Ontario. Golden Eagles are also caught in traps set for furbearing animals, but the incidences have lessened in recent years with more restrictions on leg hold traps. However, some eagles are still caught in Conibear traps and wolf snares. Fewer eagles are shot now because of education, greater restrictions on firearms and better enforcement of illegal hunting. For ID and status in Ontario, see Duncan (1990).

Crested Caracara: (CC) Accidental. Two accepted records. They might have been escapees from captivity.

American Kestrel: (AK) Our most common falcon. Numbers peak in September. The American Kestrel and the Sharpie are the two most common small hawks seen at hawkwatches. Sharpies appear like American Kestrels at times and they often fly at the same time and in the same air space. Many migrant American Kestrels seen in southern Ontario probably originate from the large clearcuts in the boreal forest which have benefited this open country species.

Merlin: (ML) Uncommon migrant. Numbers have increased dramatically since the banning of DDT in the early 1970s. Merlins begin migration in mid‐August with numbers peaking before mid‐September. They are sporadic through October and rare in November. Most birds seen are brown‐backed juveniles and adult females. Blue‐backed adult males are rarer. Merlins usually streak by, often not seen until they are past you. The occasional Merlin seen in Ontario is extremely dark, suggesting the Black Merlin subspecies suckleyi of the Pacific Northwest, which is extremely unlikely here. These dark Merlins may originate in Labrador where humid conditions have induced darker feather pigments in several species such as the Gyrfalcon, “Labrador” Great Horned Owl and Parasitic Jaeger. The Richardson’s Merlin, a pale subspecies breeding on the prairies, occurs very rarely in Ontario. For status and identification of Merlin subspecies, see Pittaway (1994).

Gyrfalcon: (GY) A very rare migrant and winter visitor, not likely to be seen before mid‐October. Identify it with caution. Sometimes confused with a goshawk, which has pointed wings during power flight. Most Gyrfalcons are either gray or dark morph individuals, but their respective juveniles are more brownish. Most Gyrfalcons seen in southern Ontario are juveniles.

Peregrine Falcon: (PG) Rare. Peregrines are making a dramatic recovery following the banning of DDT in the early 1970s. The migration peak of tundrius Peregrines comes during the last week of September and first week of October. Tundra Peregrines often appear quite different from local birds. They are smaller and paler with reduced sidebums and a pale forehead creating a less hooded appearance. Some juvenile tundrius are very sandy coloured suggesting a Prairie Falcon, but they lack the Prairie’s blackish wingpits and usually blackish centre of inner underwings.

Prairie Falcon: (PF) Casual. A short distance migrant that is not expected in southern Ontario.

Table 1. Fall Migration Period and Peak Numbers of 16 Diurnal Raptors in Southern Ontario

Species |

Migration Periods and |

Peak Numbers |

Turkey Vulture |

Mid-September to mid-November (rare winter) |

Early to mid-October |

Osprey |

Mid-August to late October (early December) |

Early to mid-September |

Bald Eagle |

September to December (rare winter) |

September |

Northern Harrier |

Late August to late November (winters) |

September |

Sharp-shinned Hawk |

Late August to late November (winters) |

September |

Cooper's Hawk |

Mid-September to early November (rare winter) |

Early to mid-October |

Northern Goshawk |

Early October to late November (winters) |

Late October to early November |

Red-shouldered Hawk |

Early October to mid-November (rare winter) |

Mid to late October |

Broad-winged Hawk |

Late August to early October (early November) |

Mid-September |

Swainson's Hawk |

Early September to late October |

Mid-September to mid October |

Red-tailed Hawk |

Mid-September to early December (winters) |

Mid-October to early November |

Rough-legged Hawk |

Early October to early December (winters) |

Late October to early November |

Golden Eagle |

Late September to December (rare winter) |

Late October to early November |

American Kestrel |

Late August to mid-November (winters) |

September |

Merlin |

Late August to early November (rare winter) |

September |

Peregrine Falcon |

Early September to late October (rare winter) |

Late September to early October (Iundrius) |

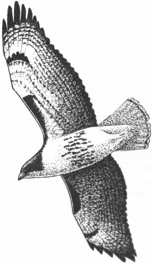

Figure 2. Adult Red‐tailed Hawk by Michael King.

Other SpeciesTop

Many birders go hawkwatching for more than just hawks. Dave Martin finds the other “visible migration” fascinating and thrilling. Dave enjoys the challenge and fun of identifying birds in flight by jizz and flight calls. Here is a sample of Dave’s highlights at hawkwatches along Lake Erie: 25000+ Blue Jays on a good day in September is guaranteed; 5000+ American Crows a day in mid‐October is not unusual; 100+ Ruby‐throated Hummingbirds per day in early September; 500+ American Goldfinches per day; Evening Grosbeaks and Purple Finches every year; European Starlings and blackbirds create a wonderful sight when migrating in flocks of l00s and 1000s, often alerting sleepy watchers to a Cooper’s, Peregrine or Merlin; American Pipits and Lapland Longspurs are much more common than birders think with 500+ pipits some days; check big flocks of Cedar Waxwings for Bohemians; up to 100 Eastern Bluebirds passing in groups of 10 to 20 birds in mid‐October; Sandhill Cranes are often seen on days when Golden Eagles migrate; one day over 600 Snow Geese flew south so high that they were nearly missed; a good day can have Tundra Swans moving east, Common Loons and Canada Geese going south and hawks moving southwest; one slow day for hawks in 1997 had 3000+ Monarchs passing per hour; dragonflies such as Green Darners pass in good numbers and are caught and eaten by American Kestrels in flight. See Jean Iron’s (1998) note on "American Kestrels and Green Darners" in OFO News 16(1):12 You can expect more than hawks at a hawkwatch!

Figure 3. Juvenile Golden Eagle by Michael King.

GlossaryTop

Abbreviations: Raptor counters use a system of two letter abbreviations: Black Vulture (BV), Turkey Vulture (TV), Osprey (OS), Swallow‐tailed Kite (ST), Mississippi Kite (MK), Bald Eagle (BE), Northern Harrier (NH), Sharp‐shinned Hawk (SS), Cooper’s Hawk (CH), Northern Goshawk (NG), Red‐shouldered Hawk (RS), Broad‐winged Hawk (BW), Swainson’s Hawk (SW), Red‐tailed Hawk (RT), Ferruginous Hawk (FH), Rough‐legged Hawk (RL), Golden Eagle (GE), Crested Caracara (CC), American Kestrel (AK), Merlin (ML), Gyrfalcon (GY), Peregrine Falcon (pG), Prairie Falcon (PF), and these for unidentified birds, UA = unidentified accipiter, UB = unidentified buteo, UE = unidentified eagle, UF = unidentified falcon, UR = unidentified raptor. See other names under Nicknames below.

Albinism: The absence of all pigments produces the very rare total albino. Partial albinos are more frequent. Albinistic individuals are seen more often in Red‐tailed Hawks than in all other hawks combined.

DDT: Abbreviation for the pesticide dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane. DDT in birds such as the Bald Eagle caused eggshell thinning and reproductive failures. DDT was banned in Canada in 1971 and the United States in 1972. Birds of prey are now showing a remarkable recovery from the effects of DDT.

Dihedral: Wings held above the horizontal forming a V‐shaped outline. Dihedrals are pronounced in the Turkey Vulture and Northern Harrier, whereas dihedrals are less inclined in the Rough‐legged Hawk and Golden Eagle. Caution: Many other species fly with slight dihedrals.

Immature: Generally has the same meaning as juvenile in species that have only one plumage before adult plumage. Juvenile is the preferred term. Immature is best used for eagles when exact age before adult is unknown.

Intergrade: An individual or population showing intermediate characters between two subspecies (races).

Juvenile: Generally has the same meaning as the term immature. Juvenile is a more precise term indicating a bird in its first full plumage. Juvenile plumage in most hawks is held for about a year before the molt to adult plumage begins.

Kettle: A kettle is group of hawks soaring in a thermal. Apparently the term kettle originated at Hawk Mountain in Pennsylvania. Observers there often referred to hawks soaring over the "kettle", a local land formation and the word kettle gradually gained its current meaning. Kettle is called a boil at some watches.

Kiting: A more or less stationary hawk in flight that is facing into a wind with an updraft.

Legal Protection: In Canada, birds of prey are under provincial jurisdiction. In Ontario, all birds of prey are protected and regulated by the provincial Fish and Wildlife Conservation Act. Additional protection is given to the Bald Eagle, Golden Eagle and Peregrine Falcon by the provincial Endangered Species Act. Both statutes are enforced by the Ministry of Natural Resources (MNR). Laws prohibiting the shooting, pole trapping and unlawful possession of birds of prey in Ontario are now strictly enforced. To report violations, contact the nearest MNR office listed in the phone book or report it to the OPP who will contact the Ministry.

Leucism: A reduction or absence of some dark pigments producing a grayish, buffy or pale individual that has a “washed out” appearance compared to normal individuals in the population.

Melanism: An excess of dark pigments producing the dark morph in many species.

Morph: This more accurate term replaces the term phase. Morphs are distinct colour types that coexist in the same interbreeding population. Morphs usually are not correlated with age. sex, subspecies or season. Unlike subspecies (races), morphs do not have scientific names.

Nicknames: BW = Broad‐winged Hawk; TV = Turkey Vulture; Gray Ghost = adult male Northern Harrier; Gos = Northern Goshawk; Sharpie and Shin = Sharp‐shinned Hawk; Tail = Red‐tailed Hawk; Shoulder = Red‐shouldered Hawk; Gyr = Gyrfalcon; Fish Hawk = Osprey.

Phase or Colour Phase: An older term now generally replaced by the preferred term morph.

Raptor: Not a taxonomic term. Refers to the diurnal birds of prey such as those covered in this article and the nocturnal raptors or owls. In recent years, however, the term raptor has become more and more associated with the diurnal birds of prey. Diurnal raptors comprise three families in North America. See discussion under Taxonomy below.

Soar: Circling with primaries spread and tail fully fanned, usually at a great height, with little flapping.

Subadult: Used mainly for eagles to indicate birds that are almost in full adult plumage, but showing traces of immature plumage.

Subspecies: A form of a species having a separate breeding range and differing in size, colour and appearance. Subspecies and race are interchangeable, Compare with morph.

Taxonomy: All the diurnal birds of prey are now split (51st Supplement to the AOU Check‐list of North American Birds, 2010) in two orders: 1. Accipitriformes, which includes the families Cathartidae (New World Vultures), Pandionidae (Osprey), and Accipitridae (Hawks, Kites and Eagles), and 2. Falconiformes, which includes Falconidae (Caracaras and Falcons).

Thermal: A rising column of warm air in which hawks soar to gain altitude. Watch for kettles forming under billowing cumulus clouds, which mark the tops of thermals.

Tuck: Raptors in a fast glide tuck (narrow) their wings and tail in a distinctive manner. The wingtips of even rounded winged species are swept back and become more pointed with many species taking on a characteristic shape.

Updraft: Wind that is turned upward along cliffs and steep shorelines used by hawks to glide.

Water Crossings: Most slow flying hawks, especially accipiters and buteos, are reluctant to cross large bodies of water where there are no thermals. They drop low to keep from being blown offshore. Hawks caught over water are subject to exhaustion from frequent flapping and to being lost in sudden fogs. Hundreds of hawks probably drown every year in the Great Lakes.

AcknowledgementsTop

For comments and valuable information, I am grateful to John Barker, Don Barnett, AlIen Chartier, Bruce Duncan, Nick Escott, Michel Gosselin, Tom Hince, Michael King, Jean Iron, Dave Martin, Ron Tozer and Mike Turner. Michael King’s art and map are most appreciated.

Suggested References Top

1999. Greater Toronto Raptor Watch. Published by the author.

1993. Hawks of Holiday Beach. A guide to their identification, occurrence, and habits at Holiday Beach Conservation Area, Ontario, Canada. Published by the Holiday Beach Migration Observatory.

1987. A Field Guide to the Hawks of North America. Peterson Series. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston.

1983. Identification of Accipiters in Ontario. Ontario Birds 1(2):43‐49.

1986. The Occurrence and Identification of Swainson’s Hawk in Ontario. Ontario Birds 4(2):43‐61.

1987. Identification of Red‐shouldered, Broad‐winged, Cooper’s and Northern Goshawks in Immature Plumage. Ontario Birds 5(3):106‐111.

1990. Identification and status of Bald Eagles, Golden Eagles, Turkey Vultures, and Black Vultures in Ontario. Ontario Birds 8(2):61‐69.

1988. Hawks in Flight. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston. My favourite hawk guide.

1995. Bird‐Finding Guide to Ontario. University of Toronto Press. Essential reference.

1999. A Guide to Point Pelee and surrounding region. Published by the author. Wild Rose Guest House, Wheatley, Ontario.

1995. Red‐shouldered Hawk Update. OFO News 13(2):8.

1998. American Kestrels and Green Darners. OFO News 16(1):12.

1990. Hawks, Eagles, and Falcons of North America. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington and London.

1989. Flight Strategies of Migrating Hawks. The University of Chicago Press. Recommended for advanced watchers.

1998. Hawk Cliff: Where do we go from here? OFO News 16(2):8‐9.

1995. Sharp‐shinned Hawk and Common Crow migration along Georgian Bay. Ontario Birds 13(2):74‐76.

(Editor). 1998. Handbook of North American Birds. Volumes 4 and 5. Yale University Press, New Haven and London. The most authoritative scientific reference on diurnal raptors.

1993. Recognizable Forms: Subspecies and morphs of the Red‐tailed Hawk. Ontario Birds 11(1):23‐29.

1994. Recognizable Forms: Merlin. Ontario Birds 12(2):74‐80".

1998. Northern Redtails. OFO News Volume 16(1):4. February 1998.

1995. A Photographic Guide to North American Raptors. Academic Press. Fabulous ID photos. See book review (Pittaway 1995) in Ontario Birds 13(2):84‐86.

1995. Toronto’s High Park. Favourite Birding Hotspots. OFO News 13(3):2‐3.