Southbound Shorebirds

By Ron Pittaway

Updated July 2010. First published OFO News 17(2):1–7, 2001. Please Ron if you have questions.

Shorebird watching is one of birding’s most pleasurable experiences. The opportunities for close observations, the identification challenges and excitement of finding rarities attract us to them. There are 50 shorebird species on the Ontario checklist. This guide treats the southbound migration of 37 shorebirds of regular occurrence in southern Ontario.

When to See ShorebirdsTop

Most shorebirds are long distance migrants. The fall migration of shorebirds begins in late June and goes to mid November or longer if freeze‐up is late. In most species, adults migrate a month or more before the juveniles (Table1). The first adult Lesser Yellowlegs and Least Sandpipers move south in late June. More adult shorebirds arrive in early July, with species diversity and numbers increasing through July. Adult numbers peak in late July followed by a sharp decrease by the second week of August. The first juvenile Least Sandpipers and Lesser Yellowlegs arrive in late July, followed soon by juvenile Semipalmated Sandpipers and Short‐billed Dowitchers in early August. By mid August, the juveniles of most species greatly outnumber adults. Total number of individuals peaks about the third or fourth week of August. Highest species counts occur from mid August to early September when it is possible to see over 20 species in a day. Numbers, especially peeps, dwindle quickly by early to mid September, but different species such as Dunlin arrive, so species diversity can remain high into early October. Shorebird numbers decrease following cold fronts in October, but your chances of seeing a rare Red Phalarope or Purple Sandpiper increase. Shorebirding ends when mudflats freeze between mid November and early December.

Lesser Yellowlegs molting adult. Photo: Jean Iron

Table 1. Main Adult Migration Period

& Average Juvenile Arrival of 18 Shorebirds.

Top

Species |

Main Adult Migration Period |

Average Juvenile Arrival Time |

|---|---|---|

Black‐bellied Plover |

Late July to early September |

Early September |

American Golden Plover |

Early August to early September |

Early September |

Semipalmated Plover |

Mid July to third week August |

Second week of August |

Greater Yellowlegs |

Early July to mid August |

Early August |

Lesser Yellowlegs |

Late June to mid August |

Late July |

Solitary Sandpiper |

Early July to mid August |

Late July |

Ruddy Turnstone |

Late July to mid August |

Mid August |

Red Knot |

Mid July to mid August (rare) |

Mid August (uncommon) |

Sanderling |

Mid July to mid August |

Mid August |

Semipalmated Sandpiper |

Mid July to mid August |

Early August |

Least Sandpiper |

Late June to mid August |

Late July |

White‐rumped Sandpiper |

Mid July to mid September |

Mid September |

Baird’s Sandpiper |

Mid July to mid August (rare) |

Mid August |

Pectoral Sandpiper |

Mid July to early September |

Third week of August |

Dunlin |

Mid September to early November |

Early September |

Stilt Sandpiper |

Early July to early August |

Second week of August |

Short‐billed Dowitcher |

Early July to early August |

Early August |

Long‐billed Dowitcher |

Mid July to mid September (uncommon) |

Mid September (rare) |

Where to See ShorebirdsTop

Sewage Lagoons: When water levels are low, sewage lagoons are ideal places to watch shorebirds. Since water levels on the Great Lakes usually stay high through July, sewage lagoons provide better habitat for most shorebirds in July. Sewage lagoons usually are excellent through August, but often become less productive in September as water levels rise again. Lake Ontario: The water level usually drops during August, creating mudflats at Dundas Marsh and Windermere Basin in Hamilton, Frenchman’s Bay in Pickering, Corner Marsh in Ajax and Oshawa Second Marsh. Shorebirding is usually excellent at Presqu’ile Provincial Park from Beach 4 to Owen Point. Lake Erie: In low water years, the entire shoreline from Turkey Point east to Fort Erie can provide a fine day’s shorebirding. Other Lake Erie hotspots are the tip of Point Pelee and the onion fields north of Pelee east of Mersea Road 19. Hillman Marsh Conservation Area near Pelee is fabulous when water levels are low. St. Lawrence River: Best spots are between Morrisburg and Cornwall along Highway 2 at Nairn Island and Hoople Bay. The widening of Hoople Creek 1 km up‐stream from the highway is often excellent in August and September. Ottawa River: Best spots are Ottawa near Andrew Haydon Park (Ottawa Beach) and the dike at Shirley’s Bay. The above locations are not a complete list.

Rock Point Provincial Park.

Photo: Jean Iron

HabitatsTop

Shorebird numbers vary from year to year mainly because of low or high water levels. The levels on the Great Lakes show a seasonal pattern, with levels falling during August and early autumn. Strong winds on the lower Great Lakes continually wash up new clusters of Cladophora algae. This mat of decaying algae is full of fly (Diptera) larvae which shorebirds find irresistible. During long periods of hot days in summer, mudflats, beach pools, and algae mats dry out, becoming less productive for shorebirds. However, strong winds are beneficial because waves and wind tides (seiches or oscillations) create new pools on beaches, reflood mudflats and soak dried algae mats, allowing invertebrates to flourish again. Sewage lagoons also produce an abundance of invertebrates. Shorebirds will turn up anywhere there is suitable habitat. Watch lakes and reservoirs for water level drawdowns. Check farm ponds, flooded fields, sod farms, freshly plowed and newly harvested fields.

WeatherTop

Check shorebird spots immediately after major storms. Thunderstorms sometimes cause fallouts of migrating shorebirds, which often depart when the weather improves. Many successive days of head winds from the south slow migration and shorebird numbers often increase gradually at favoured spots while awaiting a tail wind to depart. Cold fronts with a northwest wind often trigger migration.

Plumage, Molt and AgeTop

To identify shorebirds, especially rarer species, it helps to determine the bird’s plumage and stage of molt. Shorebirds have three distinct plumages: alternate (breeding), basic (winter) and juvenal (juvenile). See Figure 1. Learning to recognize alternate, basic and juvenal feathers is the secret to understanding molt and age in shorebirds. Alternate feathers generally are coloured and patterned; basic feathers generally are pale grey with a distinct dark shaft streak; and juvenal feathers generally have a distinct pale fringe, creating a scalloped appearance above. Adults in July and August are in worn alternate plumage or in body molt to basic plumage. Molting adults show a contrasting and messy mixture of worn alternate and fresh basic feathers. Since juveniles grow their feathers all at the same time, fresh juveniles look brand new lacking a molt contrast of old and new feathers. The first juveniles arrive in fresh juvenal plumage, while later juveniles are more faded, worn and usually show body molt to first basic (first winter) plumage. Caution: Bright fresh juveniles often cause identification pitfalls for the unwary. In molting juveniles, the new basic grey feathers contrast with the pale fringed juvenal feathers. Note that very few shorebirds are seen in full basic plumage in Ontario. Most adult shorebirds do not molt their wings and tail until reaching the wintering grounds.

Feather GroupsTop

Learn these three feather groups on a standing shorebird: wing coverts, scapulars, and tertials. They are important for identification, aging and understanding molt and age.

Annotated List of ShorebirdsTop

Black‐bellied Plover: Uncommon to fairly common migrant. A few adults mostly in alternate plumage are seen after late July. Later adults are in various stages of blotchy molt. The first juveniles arrive in early September. Some very fresh juveniles are heavily speckled with yellow (fades quickly) suggesting golden‐plovers. A few birds, usually juveniles and occasionally basic plumaged adults, linger into November. Lone standing juveniles are difficult to identify, but often a small rudimentary hind toe, absent in golden‐plovers, can be seen at close range. Prefers large mudflats, sandbars, wide beaches, and less often sewage lagoons. It sometimes mixes with American Golden‐Plovers and Killdeers on freshly plowed fields and sod farms. The plaintive three‐parted pee‐u‐weee whistle call is easy to imitate and brings flying birds in closer.

American Golden‐Plover: Uncommon migrant rarely seen before early August with a few staying to November. Adults in August are in worn alternate plumage or in blotchy molt to basic plumage. Some retain almost full alternate plumage into early September. The first juveniles arrive in early September. Fresh juveniles are much darker and richer in colour than shown in most guides. A few golden‐plovers usually mix with other shorebirds on the shorelines of the Great Lakes and less often at sewage lagoons. Occasionally flocks are seen on sod farms and freshly plowed fields, often mixing with Black‐bellied Plovers and Killdeers. Calls include a single whistled keet or a double kee‐Ieet and a quavering whistled queedle.

Juvenile Black-bellied Plover. Photo: Sam Barone

Semipalmated Plover: Common migrant from mid July to mid September with a few lingering into October. Juveniles arrive in mid August. Unlike adults they have all‐dark bills, fine scalloping on the back and a duller neckband. Prefers mudflats and sewage lagoons often with Least and Semipalmated Sandpipers. Its plaintive rising chu‐wee call is distinctive. Caution: half‐grown Killdeer has one neckband, but is downy with a long central tail streamer.

Piping Plover: Endangered species. It formerly nested on sand beaches such as Presqu’ile, Long Point and Wasaga Beach. In 2007 it re‐established breeding in Ontario at Sauble Beach and in 2008 at Wasaga Beach. It is expected to increase as a breeder given protection. Very rare fall migrant, most are lone juveniles in August and September. Call is a soft whistled peep‐loo. Always check Piping for vagrant Snowy Plover, which has dark legs.

Killdeer: Common breeder. Adults and juveniles begin gathering in early July at sewage ponds, wet pastures, sod farms, freshly plowed fields and shorelines. Adults show worn reddish brown upperparts while juveniles are greyish above, often retaining downy central tail streamers. Common call is a loud repeated kill‐dee. Fall birds are less vocal with a few lingering to freeze‐up.

American Avocet: A very rare August migrant, occasionally to early December. Most are juveniles whose cinnamon head and neck colour mimics alternate plumage. Females have more upturned bills than males, but only extremes can be reliably sexed.

Spotted Sandpiper: Common breeder at sewage ponds, lake and river shorelines. Numbers decrease sharply after mid August. A few juveniles and occasional adult still in breeding plumage linger to late September, rarely later. We do not see the basic (winter) plumage in Ontario because breeding plumaged adults and juveniles molt on winter range. Juveniles are unspotted below with narrow pale fringes to the wing coverts. They have a prominent white eyering leading to confusion with Solitary Sandpiper, but Spotted has pale legs, pale base to the bill and habit of constantly teetering its body. Common calls are a sharp pee‐weet and a series of weet notes, usually given as the bird flies with rapid shallow wing beats.

Solitary Sandpiper: Fairly common migrant from early July to late September. It is rarely seen on open shorelines, preferring the grassy edges of sewage ponds, marshes and wooded ponds. The first fresh juveniles arrive in late July. They are neatly speckled above with buffy white spots in contrast to worn adults that have lost much of their pale spotting above. This species usually molts on the wintering grounds. The Solitary is often first detected when it flushes giving a distinctive peet weet call like a Spotted Sandpiper’s but shriller.

Juvenile Semipalmated Plover. Photo: Jean Iron

Greater Yellowlegs: Fairly common migrant from early July to early November. Prefers sewage lagoons, open marshes and mudflats; much less often on open shorelines. Time of arrival and numbers fluctuate widely from year to year, it is usually much less common than the Lesser. Adults normally arrive somewhat later than Lessers. August adults are in patchy molt to basic plumage, usually with enough heavy spotting and barring below to identify them as Greaters. Unlike most shorebirds, adult Greaters are often seen in wing molt (slight gap best noted in flight) in Ontario. The first neatly spangled juveniles usually arrive in early August, contrasting with the molting adults. Late staying juveniles undergo molt to first basic (winter) plumage. Both adults in basic plumage and molting juveniles stay into November. Juveniles and most fall adult Greaters show a grey base to the bill, helping to separate them from Lessers. Greaters are often more active than Lessers, running and stabbing the water for minnows. The Greater’s loud ringing deer deer deer call differs from the Lesser’s call.

Lesser Yellowlegs: The Lesser is generally much more common than the Greater. Adults arrive in southern Ontario in late June. Numbers build quickly at sewage lagoons, becoming common by early July. They are less common along shorelines. The first neatly spangled juveniles arrive in late July, contrasting in appearance with dwindling numbers of patchy molting adults through August. Lessers are scarce by late September, whereas Greaters occur in small numbers for at least another month. This species, like other shorebirds, sometimes stands or hops on one leg with the other leg hidden in the feathers, leading one to believe that the bird has only one leg. Sewage lagoons ring with their teu teu calls, usually given in pairs, but repeated in a long series by alarmed birds. These calls are usually the first clue to a birder approaching a lagoon that suitable habitat exists. July adults are much more vocal than juveniles in August.

Willet: Rare migrant. Occasional juveniles are seen in August and September along shorelines of the Great Lakes, almost never at sewage lagoons. A Willet at a sewage lagoon is likely a godwit and a flock of fall Willets in Ontario is almost certainly Hudsonian Godwits, which show considerably white and black in flight leading to the confusion. At rest Willets often nod their heads like yellowlegs, whereas godwits do not nod. Godwits have pale‐based bills. Migrant Willets are rarely vocal in Ontario.

Upland Sandpiper: Our smallest curlew, slightly smaller than the extinct Eskimo Curlew, but with a straight bill that is slightly downcurved only at the tip. Uncommon breeding bird of pasturelands where grass is kept short by grazing. The Carden Alvar is the best place to see breeding birds and hear their curlew song and calls from late April into summer. I once saw about 75 birds in July staging on the Carden Alvar. Not often seen on migration, usually singles, but look for them from early July to mid September at sod farms and recently cut hay fields. Migrants occasionally stop at dried out sewage ponds, but usually do not return after flushing like other shorebirds. They are regular on the onion fields east of Mersea Road 19 north of Point Pelee. Migrants are sometimes detected by distinctive flight call, a liquid quit‐it, similar to a call heard on the breeding grounds. Interestingly, migrating birds usually have a full wing stroke like a Whimbrel, unlike the shallow stroke seen on the breeding grounds.

Juvenile Greater Yellowlegs molting into first basic plumage. Photo: Jean Iron

Whimbrel: Rare fall migrant (usually singles) in southern Ontario from mid July to late September, occasionally later. July birds are adults; most birds after mid August are juveniles. Most southbound Whimbrels migrate from Hudson and James Bays directly to the Atlantic Coast with their flight path across Quebec. A few are seen along the shores of the Great Lakes. Even rarer inland at sod farms and exceptional at sewage lagoons. The practiced ear often detects flying birds by their call, a rapid series of ti‐ti‐ti‐ti‐ti‐ti‐ti notes on the same pitch.

Hudsonian Godwit: This species was once thought to be on verge of extinction. In July 1942, Ontario ornithologists Cliff Hope and Terry Short found large numbers in James Bay. We now know that thousands gather in James Bay from mid July to late September. Most fly nonstop to South America. However, a few molting adults and occasionally flocks are seen from early July to early September in southern Ontario, usually after being grounded by thunderstorms. A few juveniles (rarely flocks) are regular from mid September into November, with late staying birds in molt to first basic (winter) plumage. Prefers large mudflats along the lower Great Lakes, rarer at sewage lagoons in fall. Migrants rarely call. Caution: this species is sometimes misidentified as a Willet because it shows more white in the wings and tail than expected. A flock of Willets seen in fall is probably Hudsonian Godwits.

Marbled Godwit: Very rare migrant from August to October. It prefers wide mudflats along the Great Lakes and large sewage lagoons. Migrants are rarely vocal.

Ruddy Turnstone: Fairly common migrant on sandy, rocky and algae covered shores of the Great Lakes. Rare at sewage lagoons. Adults in full breeding plumage occur from late July to mid August, sometimes later. The first juveniles arrive in mid August, becoming uncommon after mid September, occasionally into October. Juveniles are much duller (no reddish) above than adults and like them wear "a drooping brassiere." Distinctive call is a harsh cackling chut‐chut‐chut‐chut.

Red Knot: Several thousand molting adults occur in southern James Bay, but are very rare in southern Ontario from mid July to mid August. Juveniles are regular in southern Ontario, usually one to three birds at a time from mid August through September, rarely to early November when still in full juvenal plumage. One of the best places to see juvenile knots is Presqu’ile in late August and September. Migrants are rarely vocal, but flying birds sometimes give a low whistled eer‐oit.

Juvenile Whimbrel. Photo: Bill Edmunds

Sanderling: Common migrant on the sandy and algae covered shorelines of the Great Lakes. Uncommon at sewage lagoons and most inland locations. The first adults arrive by mid July. They exhibit a variety of faded and molting plumages through August. Caution: bright individuals retaining faded alternate plumage are sometimes misidentified as Red‐necked Stints. Sanderlings lack a hind toe, which is present on other sandpipers, have a striking white wing stripe in flight and give sharp jip jip calls. The first fresh juveniles arrive in mid August. They are distinctly checkered above (Figure 2), contrasting with the decreasing numbers of molting adults. Molting juveniles are common through October with a few staying until mid November. Late birds acquire first basic plumage.

Semipalmated Sandpiper: Common migrant from mid July through August with numbers dropping sharply in early September. As the season progresses, adults molt some scapulars showing a mixture of old alternate and new basic feathers. Juveniles begin arriving in early August and soon become commoner than departing adults. Juveniles are neatly scaled above with buff, sometimes a bright rufous leading to confusion with Western. Juveniles do not molt in Ontario helping to separate them from Westerns. Both Semipalmated and Western Sandpipers have small basal webs between the front toes. You can see often these webs with a good telescope (Figure 3). Least Sandpiper and stints lack webs. Caution: Some eastern breeding Semipalmateds have extremely long bills appearing like Western Sandpipers. Separate them by plumage, molt and call differences. Call is a short harsh chert.

Western Sandpiper: Look for the locally rare Western Sandpiper among flocks of Semipalmated and Least Sandpipers. A few adult Westerns are seen from late July to mid August. Westerns are more regular in areas around Point Pelee than elsewhere in the province. The molt of adult Westerns is earlier and more extensive than adult Semipalmated Sandpipers. Look for a mixture of contrasting old red/black alternate and new grey basic feathers in the scapulars and scattered black arrowhead marks on the flanks, both indicators of an adult Western in mid summer. By late August, adult Westerns are in almost full basic plumage, unlike adult Semipalmateds. A few juvenile Westerns occur after mid August. Compared to juvenile Semipalmateds, they have the combination of much brighter red inner scapulars and longer drooped bills. Like adults, juvenile Westerns molt earlier than juvenile Semipalmateds. By late August, juvenile Westerns show many new grey basic feathers in the scapulars, whereas juvenile Semipalmateds are still mostly in full juvenal plumage. Occasionally young Westerns occur in October. These first basic Westerns look like small Dunlins. Cautions: Novices sometimes misidentify bright reddish juvenile Least Sandpipers as Westerns because the Least’s bill also droops at the tip. Molting juvenile Dunlin with their reddish scapulars and drooping bills, and both adult and juvenile White‐rumped Sandpipers, are also mistaken for Westerns. Call note is a high pitched chee‐rp like a cross between a Least and White‐rumped Sandpiper call.

Juvenile Western Sandpiper. Photo: Jean Iron

Least Sandpiper: Common migrant. Smallest sandpiper in the world. The first adult Least Sandpipers arrive south in late June and are common through July, but adult numbers dwindle by mid August. Worn adults in late summer show some new basic scapulars. The first juveniles arrive in late July and by mid August greatly outnumber adults. Numbers drop off sharply from early to mid September. A few juveniles linger to mid October or later, sometimes showing first basic scapulars. In all plumages, Leasts can be told from the Semipalmated Sandpipers by their yellowish (adults) to greenish (juveniles) legs. Caution: the greenish legs of juveniles may appear black in poor light or if coated with muck. Leasts are easily identified by their distinctive flight call, a high thin kree‐eet, often drawn out.

White‐rumped Sandpiper: Common in James Bay, but fall migration route is mostly east of Ontario. Look for a slightly larger and more elongated peep in flocks of Semipalmated and Least Sandpipers. Such birds are usually White‐rurnped or a Baird’s Sandpipers. A few molting adults are seen regularly from mid July to mid September. Juveniles usually occur in larger numbers than adults, but rarely arrive before mid September. They acquire considerable first basic plumage through October with the occasional bird staying to freeze‐up. Call is a squeaky mouse‐like jeet, often the first clue to its presence in a flock of peeps. Note: Standing White‐rumps do not show a white rump patch because it is hidden by the folded wings.

Baird’s Sandpiper: Worn adults in slight molt are rare from mid July to mid August. Juveniles are much more frequent than adults, usually singles with rarely more than five together. Juveniles arrive early to mid August and are regular through October, occasionally into November. Late juveniles do not appear to be molting. Juveniles are scaly above and most are very buffy, but a few juveniles and adults are much greyer. Baird’s has a distinctive horizontal posture. Flying birds give a reedy kreep call.

Juvenile Least Sandpiper. Photo: Jean Iron

Pectoral Sandpiper: Fairly common migrant. Adult males arrive in mid July. Males are larger than females, sometimes evident in the field. Unlike most shorebirds, the males (not the females) migrate when the young hatch and females tend the young. Some July males seen in southern Ontario show a sagging lower neck bib, evidence that they are recently courting males with inflated sacs. On the nesting grounds, hooting males inflate their throats immensely. The first bright juveniles arrive in mid August looking like giant juvenile Least Sandpipers. Juveniles are best told from adults by the bold white lines on the back and bright tertial edges. Juveniles are sometimes common through September and October with some into November. Both adults and juveniles show little signs of molt in Ontario. In flight, Pectorals give a grating reedy kriek, sharper than the Baird’s.

Purple Sandpiper: This very late migrant usually does not appear in southern Ontario before mid October. Unlike most shorebirds except the Dunlin, many adult and most juvenile Purple Sandpipers molt in the Arctic before migrating south. Normally seen as singles or very small numbers in southern Ontario with a record 57 at Presqu’ile in December 1998 during a warm fall and low water period. One or two occasionally winter above Niagara Falls. All birds in southern Ontario have been in first basic plumage, aged by bright pale‐fringed juvenal wing coverts. Preferred habitats are wave‐washed rock ledges and rock jetties. Sometimes joins Sanderlings and Dunlins on algae mats and gravel beaches.

Purple Sandpiper in first basic plumage. Photo: Brandon Holden

Dunlin: A late migrant, very few arrive in southern Ontario before mid September. Usually common through October and sometimes into November. Both adult and juvenile Dunlins stop over near the breeding grounds such as James Bay to molt to basic (winter) plumage before migrating. The odd molting juvenile arrives from mid August to mid September. Since most birders are not familiar with molting juveniles, they are mistaken for molting adults because they have dark spots on the sides of the belly suggesting the adult’s belly patch. Look for the juvenile’s rufous fringed scapulars and tertials. First basic birds often retain enough traces of juvenile plumage, especially the bright edged tertials. Most fall Dunlin aged in southern Ontario were in first basic plumage, suggesting that adults go directly to the Atlantic Coast. Caution: Molting juvenile Dunlins are mistaken for Western Sandpipers because they have drooped bills and reddish scapulars. Distinctive flight call is a loud slurred tree‐ur that carries a long distance. Note: An extremely small and short‐billed Dunlin in heavily worn alternate plumage was seen at Hamilton on 31 July and I August 1994. It was either the subspecies arctica or schinzii as both small subspecies breed in Greenland.

Curlew Sandpiper: The occasional adult in alternate plumage or molting adult is seen in Ontario from mid July through August. Watch for juveniles in September and October with Dunlin, White‐rumped or Pectoral Sandpipers.

Juvenile Dunlin molting into first basic plumage. Photo: Jean Iron

Stilt Sandpiper: Uncommon migrant, usually mixed in with other shorebirds. The first worn adults appear at sewage lagoons in early July. Less frequent along shorelines. Late July and early August adults are in body molt to basic plumage, with some adults completing body molt before departing in mid August, rarely later. The first juveniles appear in early to mid August, with later birds in body molt to first basic plumage. A few young birds stay to mid October. Stilt Sandpipers often associate with Lesser Yellowlegs and Short‐billed Dowitchers. Old‐timers thought that Stilt Sandpipers were hybrids between yellowlegs and dowitchers. Stilts often suggest a dowitcher by plunging their whole head and neck underwater. Their long bill drooped at the tip is a good field mark. Migrants are rarely vocal.

Buff‐breasted Sandpiper: Rare migrant, usually singles or a few birds together, but occasionally small flocks are seen at favoured locations such as Point Pelee. Adults are extremely rare in late July and early August. Juveniles occur regularly from mid August to mid September with a few October records. Look for them at sod farms, large sewage lagoons and wide beaches along the Great Lakes, such as at Presqu’ile. One of the best places to see them is the onion fields adjacent the north dike of Point Pelee National Park. Early in the day is best when the heat haze is minimal. A scope is essential. You can often pick them out by their unusual high stepping gait and head bobbing. Single migrants are usually silent.

Ruff: Very rare migrant from July into September. Most occur at sewage lagoons with Lesser Yellowlegs. Males molt their ruffs early, appearing more like females. Ruffs can be picked out among yellowlegs by their orangy legs and some have greenish legs. Watch for juveniles after early August. The female Ruff is sometimes called a reeve, which is an Old World name. It is not mentioned in the American Ornithologists’ Union and British Ornithologists’ Union checklists or in leading shorebird specialty books.

Short‐billed Dowitcher: Fairly common migrant from early July to mid September, rarely later. Adults in alternate plumage occur July to early August, rarely later. Two subspecies and intergrades occur in Ontario: nominate griseus and hendersoni. These two subspecies in alternate plumage are often separable in the field. Hendersoni is the much commoner subspecies except in extreme eastern Ontario. Some intergrades (intermediates) occur. The thin breeding population in northern Ontario is the main area of intergradation. Juveniles arrive early August and are seen to mid September, rarely later. Very bright colourful juveniles are sometimes mistaken for adults. Learn distinctive call, a rapid tu‐tu‐tu, suggesting a soft Ruddy Turnstone.

Juvenile Stilt Sandpiper molting into first basic plumage. Photo: Rick Lauzon

Long‐billed Dowitcher: Much rarer in the province than the Short‐billed. Most adult and juvenile Long‐bills migrate about a month later than same age Short‐bills. Adults may be present in southern Ontario from mid July to mid September. Summer Long‐bills in worn alternate plumage look like hendersoni Short‐bills. There is a difference in molt. Adult Short‐bills do not show signs of molt in Ontario, whereas adult Long‐bills usually do. An adult dowitcher in body molt in summer is a Long‐billed. Some adults also show active wing molt with a gap in the flight feathers evident in flight. Short‐billeds never show wing molt in Ontario. Juvenile Long‐bills are much more frequent than adults. They normally arrive by mid September (very rarely late August) and occur through October. A dowitcher seen after mid September is likely a Long‐billed. In all plumages, Long‐billeds usually have a conspicuous pale lower eyering. The Long‐billed’s eyering is thicker and more even in width compared to the thinner and often uneven lower eyering of the Short‐billed. The eyering difference is not diagnostic, but an indicator of the species. Learn the diagnostic call of the Long‐billed, given standing and flying, a single thin whistled peep, sometimes repeated.

Wilson’s Snipe: Common breeder staying to mid October with a few up to freeze‐up Usually hides by squatting or skulking near reeds in sewage ponds and marshes where small groups gather after nesting. Rarely seen in the open. Best told from dowitchers by their boldly striped heads and backs. Adult and juvenile plumages are very similar. Flushes in a zigzag flight calling a raspy scape.

American Woodcock: Fairly common breeder. Secretive woodland sandpiper when not displaying at dusk and dawn from mid March into June. Never seen at sewage ponds or mudflats. Rarely seen unless flushed, or seen at dawn and dusk flying between feeding and roosting sites. Wings make a distinctive twittering whistle.

Wilson’s Phalarope: Uncommon migrant and rare breeder. Most occur at sewage lagoons. Adult females are extremely early fall migrants, rarely seen after late June in Ontario. Males tend young until about mid July and most migrate south by early August. Birds seen after mid July are mostly juveniles molting into first basic plumage. A few are in full juvenal plumage in mid August, perhaps later hatched birds from James Bay. Occasional yearlings are seen in September and October; they are in grey first basic plumage. The legs are yellow in juveniles and first basic birds. Phalaropes habitually swim, but all shorebirds can swim. Sometimes a swimming Lesser Yellowlegs is misidentified as a Wilson’s Phalarope. Wilson’s swim much less than the other two phalaropes, often preferring to walk in shallow water with other small shorebirds. On hot summer days, Wilson’s Phalaropes often run on the shore with their bills pointed down and tails pointed up, actively snapping up swarming insects. This behaviour allows them to be identified at a long distance. Breeders give pig‐like grunts but migrants are usually silent.

Juvenile Long-billed Dowitcher molting into first basic plumage. Photo: Jean Iron

Red‐necked Phalarope: Adults are very rare from mid July to mid August. Earlier arriving females are mainly in alternate plumage or molting whereas late males are well into basic plumage. A few juveniles showing little or no molt are regular from early August to late September, rarely later. Usually seen swimming at sewage lagoons often with ducks. Rarely on mudflats and shorelines with other shorebirds, but is regular offshore on the Great Lakes. A phalarope seen after mid October is more likely the next species.

Red Phalarope: Adults mostly in alternate (breeding) plumage or molting are extremely rare in mid summer. Usually seen near the Great Lakes and rarely at sewage lagoons. A few juveniles are regular every year. Most juvenile Reds migrate much later than juvenile Red‐necked Phalaropes. However, early juveniles may arrive in late August when Reds are not expected by most birders. September birds are in body molt, showing a mixture of bright juvenile and grey first basic (winter) feathers. Juvenile and molting juvenile Reds are sometimes mistaken for Red‐necked Phalaropes because they appear streaked on the back. One bird on the 24 October 1992 at Frenchman’s Bay in Pickering was in almost full juvenile plumage, with some grey basic scapulars. However, most are in first basic plumage by late October, except for telltale retained bright edged juvenile tertials. Reds sometimes linger into early December. In flight, juvenile and basic Red and Red‐necked Phalaropes look like Sanderlings with their conspicuous white wing stripes. Call is a whit like a Sanderling, but higher and thinner.

Juvenile Red-necked Phalarope. Photo: Saul Bocian

Shorebird FactsTop

Call Notes: Learn call notes because most shorebirds can be identified and are often first detected by their distinctive calls.

Eskimo Curlew: The Eskimo Curlew was probably a regular fall migrant in Ontario. Specimens were taken in Toronto in 1864, near Kingston on 10 October 1873, and near Hamilton (ROM specimen undated). It had almost disappeared by the early 1890s, about 120 years ago. The last Canadian specimen was taken on 29 August 1932 at Battle Harbour, Labrador. Accepted sightings in Texas from 1945 to the 1960s never recorded more than two birds. Last photographed delete (one) in March and April 1962 near Galveston, Texas. Last specimen (adult) shot on 4 September 1963 in Barbados, West Indies. I have often wondered if the individual in the 1962 Texas photo and the last specimen are the same bird since likely only three extremely old Eskimo Curlews were alive in 1963. No confirmed sightings since the 1960s. Later reports were probably juvenile Whimbrels with short bills that were still growing or they were vagrant Little Curlews. Sadly, the Eskimo Curlew has been extinct for almost 50 years.

Eurasian Vagrants: July into August is the best time for vagrant adult Eurasian shorebirds because it is the main migration period of adults leaving the Arctic breeding grounds and they are still in alternate plumage or molting. Watch for Wood Sandpiper (overdue), Spotted Redshank (25 July 1976, 18‐24 July 1990, 21 August 1998), Little Stint (10 July 1979, 25 July 1992), Red‐necked Stint (overdue), Sharp‐tailed Sandpiper (20 August 1988), Curlew Sandpiper (July/August) and Ruff (annual). Juvenile Eurasian shorebirds migrate in August and September like North American juveniles, but there are fewer records than adults partly because juveniles are harder to detect.

Failed Breeders: Most adult shorebirds do not stay long on the breeding grounds after nest failure or loss of chicks. Some very early or earlier than normal first migrants in full alternate (breeding) plumage may be failed breeders. However, adults of most species appear at the same time every year suggesting that the “failed breeders” explanation is questionable in many cases.

Females Migrate First: Most shorebirds migrate south in three distinct waves: females, males, juveniles. Female shorebirds migrate first in most species. They depart soon after the young hatch leaving the males to raise the young. The males depart 2‐3 weeks later when the juveniles have grown. The juveniles of most species migrate shortly after the males, but some juveniles such as the Red Knot stay longer near the breeding grounds to fatten before migration.

First Year Shorebirds: Many shorebirds, especially the larger species, do not breed in their first full summer. They summer on or near the wintering grounds. However, some may appear in southern Ontario, usually after the main northward migration, still in basic (winter) or partial alternate (breeding) plumage.

Hybrids: Shorebird hybrids are exceedingly rare. Best known hybrid is Cox’s Sandpiper (no Ontario records) which is a Curlew x Pectoral Sandpiper, verified by molecular analysis. A probable White‐rumped Sandpiper x Dunlin hybrid was at Hillman Marsh near Point Pelee in May 1994. Another sandpiper that appeared to part Dunlin was at Presqu’ile in August 1997, and a second probable White‐rumped Sandpiper x Dunlin was at Rock Point in August 2008.

Peeps: These are sparrow‐sized sandpipers in the genus Calidris. Ontario peeps include the Semipalmated Sandpiper, Western Sandpiper, Little Stint, Least Sandpiper, White‐rumped Sandpiper and Baird’s Sandpipers, but not the larger Pectoral Sandpiper. Peeps include all the stints.

Stints: July is the best month to look for vagrant Little Stint and Red‐necked Stint (overdue in ON), when they are still mostly in worn alternate plumage. Stint is the Old World name for the world’s seven tiniest sandpipers in the genus Calidris. Three North American peeps are stints: Semipalmated, Western and Least Sandpipers, but stint does not include the two largest peeps, White‐rumped and Baird’s Sandpipers. All stints are peeps, but not all peeps are stints.

Shorebirds and Hawks: Northern Harriers and Accipters often flush shorebirds, but they usually return to the same spot. However, when Merlins and Peregrine Falcons are hunting, shorebirds become extremely nervous and often depart or change their feeding patterns and roosting areas. Disturbance causes some species such as the Semipalmated Sandpiper to leave stopover areas before they have properly fattened for long migrations, often over open ocean. The increasing numbers of introduced Peregrines are now a major conservation concern for shorebird managers in southern Canada and the United States.

Telescopes: A high quality telescope is essential for studying shorebirds. Choose a scope with a minimum 77 mm objective lens. Get high definition glass to avoid regretting your purchase. Choose a fixed wide 30 power eyepiece and avoid fixed 40, 60 or higher as your only eyepiece, or a 20‐60X zoom lens which is so versatile.

Waders: Name used by Europeans for shorebirds. Wader in North America normally means long‐legged waterbirds such as egrets and herons.

Vagrants: The following 11 species have been recorded fewer than 10 times in Ontario: Mongolian Plover, Snowy Plover, Wilson’s Plover, American Oystercatcher, Spotted Redshank, Wandering Tattler, Slender‐billed Curlew, Long‐billed Curlew, Black‐tailed Godwit, Little Stint and Sharp‐tailed Sandpiper.

Red Knot worn adult. Photo: Ken Newcombe

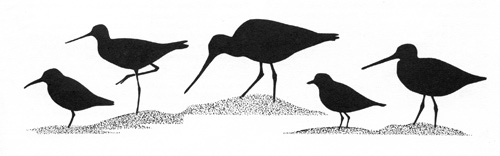

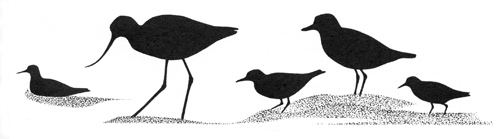

Shorebird QuizTop

Many shorebirds can be identified to species or genus by their distinctive shapes. Try these two quizzes of shorebird silhouettes. Answers at end after Acknowledgements.

Silhouette Quiz 1 by Michael King.

Silhouette Quiz 2 by Michael King.

Best Shorebird ID BooksTop

National Geographic Field Guide to the Birds of North America. 2006. Fifth Edition. National Geographic, Washington, D.C. Best field guide to shorebird ID and plumages.

Chandler, R.J. 2009. Shorebirds of North America, Europe and Asia. Princeton University Press. A gem with photos of juveniles through adults.

O’Brien M, R. Crossley, and K. Karlson. 2006. The Shorebird Guide. Houghton Mifflin Company. Boston and New York. Another gem with photos of all plumages.

Paulson, D. Shorebirds of North America: The Photographic Guide. 2005. Princeton University Press. Another gem with photos of all plumages.

AcknowledgementsTop

I thank Ken Abraham, Bob Curry, Bruce Di Labio, Earl Godfrey, Michel Gosselin, Brian Henshaw, Tom Hince, Jean Iron, Kevin McLaughlin, Guy Morrison, Ken Ross, Don Sutherland, Ron Tozer and Mike Turner. Jean Iron was very helpful with this updated version. Michael King and Peter Burke kindly provided the illustrations.

Shorebird Quiz AnswersTop

Silhouette Quiz 1 from left to right are Dunlin, Greater Yellowlegs, godwit, Charadrius plover, dowitcher.

Silhouette Quiz 2 from left to right are Red‐necked Phalarope, American Avocet, Spotted Sandpiper, Black‐bellied Plover, peep or stint.