| Where and When to See Warblers | Table 1. Point Pelee Migration Times | Annotated List of Spring Warblers |

| Notes and Remarks | Warbler Resources |

Spring Warbler Migration Guide

By Ron Pittaway

Published in OFO News 19(1):1–9, 2001. Updated April 2012. Please Ron if you have questions.

This guide is an annotated list of the 43 species of warblers recorded in Ontario. It gives the best places and times to see the spring migration of warblers in southern Ontario, with a focus on Point Pelee. The guide provides information on identification, songs, call notes, habitat, behaviour, tips on finding rare and secretive species, and a migration table for Point Pelee.

Where and When to See WarblersTop

Where To See Warblers: The best places to see warblers in spring are the migrant traps on the shores of the Great Lakes. Tree leaves emerge later at many peninsula and shoreline hotspots because the cold water of the Great Lakes chills the air, slowing growth and making for easier viewing when nearby inland areas are fully leafed out. Always take a warm coat, hat and gloves to Point Pelee in May because the temperature at the Tip is often much colder than the nearby Visitor Centre. Lake Erie: The best spots are Point Pelee, Pelee Island, Rondeau Provincial Park and Long Point. Lake Ontario: Cootes Paradise and Woodland Cemetery in Hamilton; Bronte Woods in Oakville; High Park, Toronto Islands and Leslie Street Spit in Toronto; Thickson’s Woods in Whitby; Darlington Provincial Park, Presqu’ile Provincial Park and Prince Edward Point. Ottawa: Britannia Woods in Ottawa’s west end is a migrant trap surrounded by the city and Ottawa River. Note: The above locations are just some of the dozens of areas to watch spring warblers. Any woodlot or ravine in May will have migrant warblers to watch; one need not go to a hotspot to enjoy warblers.

When To See Warblers: Spring warbler migration begins in early April with the return of Yellow‐rumped and Pine Warblers and a few Louisiana Waterthrushes. During peak migration in mid‐May, expect to see and hear at least 20 species of warblers in a day. The peak at Point Pelee usually is between the 10 and 15 May. In good years, birders can see over 30 species in a day at Point Pelee. Blackpoll and Connecticut Warblers migrate in late May. Migration extends into early June, with late migrating first year females. These non‐singing females are hard to see under thick leaf cover. See Table I for peak abundance and early and late dates for 36 regularly occurring warblers at Point Pelee.

Best Time of Day: The late Jim Baillie, ornithologist at the Royal Ontario Museum, said that the best time of day to see spring warblers is between 7:00 and 9:00 a.m. The sun rises early in May, but one must wait until 7:00 for the sunlight to warm emerging leaves and insects. Warblers sing more as it warms up. However, seeing warblers is not restricted to just early morning; migrating warblers are active almost any time of day, particularly if they are hungry during cold weather. At Point Pelee, late afternoons can be fantastic on calm days along the west beach.

Warbler Weather: Fallouts are mass groundings of migrants that come north with warm (often moist) airflows from the Gulf of Mexico. Major fallouts occur during two types of weather conditions. First, when waves of migrants meet cold northwest winds that ground large numbers of birds. Some cold days in May, Point Pelee is swarming with warblers desperate to find insects to eat. These hungry and exhausted warblers often forage low and in the open. Birders will get incredible views, but be sure to stay on the marked paths and do not chase the birds. Many insect‐eating birds starve during prolonged cold spells in May. Second, big waves also arrive on warm fronts with periods of light rain starting after midnight, which ground migrants. The following morning is often warm and cloudy with periods of rain, but the birding is fabulous. These migrants usually are not stressed because the weather is warm. Numbers then dwindle after fallouts; the second day is often 50‐70%; the third day is 25‐40% and then 10‐20%, followed by a several days of low numbers before another big wave. There are many quiet days during the normal migration time in May. Flyovers are the opposite of fallouts. During periods of warm airflows from the south and clear night skies, northern warblers do not stop in large numbers at Point Pelee or elsewhere. They continue north on a wide front. Flyovers make for poor warbler watching, but they are better for the migrating birds, allowing them to arrive safely at their breeding grounds under ideal weather conditions.

Spring Overshoots: One of the best times to visit Point Pelee is in late April following a front of warm air from the Gulf of Mexico. These early warm fronts often bring southern specialties that have overshot their breeding range, such as Yellow‐throated Warbler, Worm‐eating Warbler, Louisiana Waterthrush, Kentucky Warbler, and Hooded Warbler. Overshoot species and numbers vary from year to year, but these southern warblers are never common.

Warbler Numbers: We have all heard of huge numbers of warblers at Point Pelee, but these are unusual events. Some springs, thousands of migrants are grounded in southern Ontario by cold fronts or wet weather. Other springs, low numbers are seen because of good flyover weather.

Reverse Migration: This spectacle at Point Pelee is worth seeing, but major reverse migrations happen only a few times each spring. Reverse migrations always occur against a light to moderate south wind, usually on sunny days. They normally begin about 7:00 a.m. and go to 10:00 a.m. or rarely until noon. Reverse migrations at the Tip offer a wonderful opportunity to learn flight ID of small landbirds and to watch for rarities. During reverse migrations at Point Pelee (and at the southern tip of Pelee Island), streams of small birds including warblers are seen flying south through and over the last trees at the Tip, before flying out over Lake Erie. Sometimes birds pause for a moment in the last trees. Many small birds go out only a short distance over Lake Erie, returning to the Tip to try again several times. Other birds leave the Tip, appearing to head towards Pelee Island, but they often curve back northward to land along the west beach. Some birds probably reach Pelee Island and/or Ohio. One theory says this reverse migration comprises disoriented birds in early morning that are following the shoreline of Point Pelee to the Tip. Another theory says that some of the birds in reverse migrations have gone too far north (overshot) and are returning south. Lewis (1939) described a major reverse migration on 12 May 1937 at the southern tip of Pelee Island. At 7:00 a.m., Lewis noted that a fresh wind was blowing from the south at 15 miles an hour. The birds were flying into the wind out over the water toward the next island, Middle Island. He concluded that “many of the birds that were flying south from Pelee Island that morning, such as the Blue‐headed Vireos, Magnolia Warblers, Cape May Warblers, Myrtle Warblers, Bay‐breasted Warblers, Blackpoll Warblers, and Pine Siskins, do not nest in the regions lying southward from the island and therefore were not heading toward the destination of their migration.” However, a few species, such as Summer Tanager, may be “southern overshoots” that are returning south. The causes of reverse migrations at Point Pelee and Pelee Island remain speculative.

Warbler Species Record: The record for the highest number of warbler species recorded in one day at Point Pelee is 34 species (Wormington 1979). This record was set 9 May 1979, independently the same day by Tom Hince, Don Sutherland and the late Dennis Rupert, making Point Pelee the warbler capital of North America. The Point Pelee Checklist has 42 warbler species of which 36 species are seen most years. Point Pelee, ironically, has only four regularly breeding warblers: Yellow Warbler, American Redstart, Common Yellowthroat, and Yellow‐breasted Chat.

Cape May Warbler

Photo: Rick Lauzon

Golden-winged Warbler

Female

Photo: Frank and Sandra Horvath

Blackburnian Warbler

Photo: Daniel Cadieux

Canada Warbler

Photo: Barry Cherriere

Magnolia Warbler

Photo: Sam Barone

Table 1. Point Pelee: Spring Migration of 36 Warblers of Regular OccurrenceTop

Species |

Peak Migration |

Early and Late Dates |

Blue‐winged Warbler |

First three weeks of May |

Mid‐April to early June |

Golden‐winged Warbler |

Second week of May |

Early‐May to early June |

Tennessee Warbler |

Second and third weeks of May |

Mid‐April to early June |

Orange‐crowned Warbler |

First two weeks of May |

Mid‐April to late May |

Nashville Warbler |

First three weeks of May |

Mid‐April to late May |

Northern Parula |

Second week of May |

Late April to early June |

Yellow Warbler |

First two weeks of May |

Mid‐April to summer (breeds) |

Chestnut‐sided Warbler |

Second and third weeks of May |

Early May to mid‐June (has bred) |

Magnolia Warbler |

Second to fourth week of May |

Late April to mid‐June |

Cape May Warbler |

Second and third weeks of May |

Late April to late May |

Black‐throated Blue Warbler |

Second and third weeks of May |

Late April to early June |

Yellow‐rumped Warbler |

Late April to third week of May |

Late March to early June |

Black‐throated Green Warbler |

First three weeks of May |

Mid‐April to mid‐June (may breed) |

Blackburnian Warbler |

Second and third weeks of May |

Late April to mid‐June |

Yellow‐throated Warbler |

Mid‐April to mid‐May |

Early April to late May (very rare) |

Pine Warbler |

Mid‐April to early May |

Late March to late May (has bred) |

Prairie Warbler |

Late April to late May |

Mid‐April to late May (rare) |

Palm Warbler |

First week of May |

Mid‐April to late May |

Bay‐breasted Warbler |

Second and third weeks of May |

Early May to mid‐June |

Blackpoll Warbler |

Third and fourth weeks of May |

Early May to mid‐June |

Cerulean Warbler |

Second and third weeks of May |

Mid‐April to early June (has bred) |

Black‐and‐white Warbler |

First three weeks of May |

Mid‐April to mid‐June |

American Redstart |

Second week May to early June |

Late April to summer (breeds) |

Prothonotary Warbler |

Throughout May |

Late April to summer (rare, has bred) |

Worm‐eating Warbler |

Mid‐April to late May |

Mid‐April to summer (rare) |

Ovenbird |

Second to fourth week May |

Late April to early June |

Northern Waterthrush |

First three weeks of May |

Late April to early June |

Louisiana Waterthrush |

Second week April to third week May |

Late March to summer (rare, has bred) |

Kentucky Warbler |

Throughout May |

Mid‐April to late May |

Connecticut Warbler |

Last week of May |

Mid‐May to early June |

Mourning Warbler |

Mid to late May |

2nd wk May to mid June (may breed) |

Common Yellowthroat |

Throughout May |

Late April to summer (breeds) |

Hooded Warbler |

Mid‐April to early June |

Early April to summer |

Wilson’s Warbler |

Last two weeks of May |

Early May to Mid‐June |

Canada Warbler |

Last two weeks of May |

Early May to Mid‐June |

Yellow‐breasted Chat |

Second week of May |

Late April to summer (rare, breeds) |

Male Hooded Warbler by Peter Lorimer.

Black-throated Green Warbler

Female

Photo: Sam Barone

Cape May Warbler

Female

Photo: Brandon Holden

Mourning Warbler

Photo: Tom Thomas

Palm Warbler

Photo: Sandra and Frank Horvath

Annotated List of Spring WarblersTop

Warblers are listed in official checklist order. See Table 1 for best times to see species of regular occurrence at Point Pelee.

Blue‐winged Warbler: An uncommon migrant the first three weeks of May. Range is expanding north in recent years. Habitat is a mixture of usually dry overgrown weedy and shrubby fields, preferring to feed low in small aspens or birches. In spring, often investigates clumps of dry dead leaves still hanging on shrubs. Listen for the male’s buzzy two‐parted beeee‐bzzz song with second part usually lower. Sings from a medium to high perch, not moving much, making it reasonably easy to find. Note: Blue‐winged and Golden‐winged Warblers sometimes sing the song of the other species.

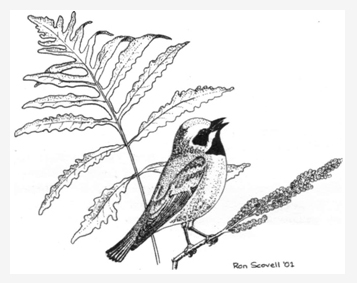

Golden‐winged Warbler: An uncommon migrant during the second and third weeks of May. Before 1930, the northern limit of its range was extreme southwestern Ontario. Over the past 70 years, its range has expanded north and east to the Ottawa River and north shore of Lake Huron (McCracken 1994). Preferred breeding habitat is dry or moist overgrown fields, but found more often in wet alder thickets than the closely related Blue‐winged. Male’s song is a buzzy bee bz-bz-bz with first note highest. Song is reminiscent of a distant Clay‐colored Sparrow. Singing male at a distance looks like a chickadee. Note: Increasing numbers of Blue‐winged Warblers are spreading north into the range of the Golden‐winged Warbler. Hybridization and habitat changes could eliminate Golden‐winged Warblers in Ontario, unless some Golden‐wings can maintain a separate breeding range (McCracken 1994). See Brewster’s and Lawrence’s hybrids below.

Brewster’s Warbler (hybrid): Rare. This is the dominant first generation hybrid between Blue‐winged and Golden‐winged Warblers. Every spring, several are seen at Point Pelee and elsewhere in southern Ontario. Brewster’s tend to sing more like Golden‐wings. Most Brewster’s have yellowish wingbars and a touch of yellow on the breast. Some Brewster’s are pure white below.

Male Golden-winged Warbler on Sensitive Fern by Ron Scovell.

Lawrence’s Warbler (hybrid): Very rare. This is a much rarer recessive second or later generation hybrid between Blue‐winged and Golden‐winged Warblers. Usually one or two are seen each spring at Point Pelee. Lawrence’s tend to sing more like Blue‐wings. Female Lawrence’s are duller than males, with gray throat and sides of head. A few variant Lawrence’s lack the black or gray throat. Caution: the much larger first year male Orchard Oriole is often misidentified as a Lawrence’s Warbler at Point Pelee (Hince 1999).

Tennessee Warbler: Common migrant in mid‐May, usually seen medium to high in deciduous trees. Tennessees look like slim vireos, but their active movements and thin pointed bills should help avoid confusion. Distinctive song is a fast paced, loud, three‐parted staccato tip tip tip che che che ti ti ti ti ti ti ti ti ti sounding like a sewing machine. Songs repeated quickly one after another. Suggests slower two‐parted song of Nashville, but Tennessee is louder, faster and repeated more often. Often sings from inside the foliage, making it hard to see. Note: John James Audubon (1785‐1851) saw only three Tennessee Warblers, indicating that large outbreaks of Spruce Budworm were probably rare in the uncut boreal forest of Audubon’s time.

Orange‐crowned Warbler: An uncommon migrant from late April to mid‐May. This olive‐green warbler prefers deciduous thickets and tall shrubbery about eye level. The orange crown patch is usually concealed. Look for a split eye‐ring and blurry streaks below. Pishing brings it in quite well. Listen for nondescript and easily overlooked trilling song that rises or falls at the end.

Nashville Warbler: Common migrant during the first three weeks of May. Not secretive. Sometimes confused with Connecticut Warbler by beginning birders, but Nashvilles usually feed from medium to high up, often in the open. However, Nashvilles feeding low on cold days in May are a pitfall for those wanting to see a Connecticut. Nashville has a bold white eyering similar to Connecticut, but it also has a yellow throat and a whitish lower belly separating the yellow undertail coverts. Song is a slow two‐parted seebit seebit seebit ti ti ti, differing from the faster and more staccato three‐parted song of the Tennessee.

Virginia’s Warbler: Extremely rare vagrant. Only three Ontario spring records for this warbler of the southwestern United States, two at Point Pelee and one at Pelee Island. Identify with extreme caution.

Northern Parula: An uncommon to rare migrant during the second and third weeks of May. Often first detected by its buzzy rising trill zeeeeeeeeee‐WIP, ending abruptly louder. Alternate song, usually sung more on the breeding grounds, is also a buzzy rising trill zh‐zh‐zh‐zheeeeee. Usually sings and feeds from a medium to high perch near the tips of branches. Sometimes feeds by clinging upside‐down, showing its greenish yellow back patch.

Yellow Warbler: This abundant species arrives suddenly in numbers in early May. Prefers open willows a nd shrubbery near water. Males usually sing from exposed perches at medium heights. Song is a rapid lively tseet tseet tseet tseet setta wee see, somewhat like a Chestnut‐sided without the emphatic ending. Both males and females fly around actively giving loud metallic chip call notes. On females, the diagnostic yellow patches on inner webs of tail feathers separate them from other “yellow” warblers.

Chestnut‐sided Warbler: Common migrant during second and third weeks of May. Usually forages at low to medium heights in deciduous forest edges and openings. Famous primary song goes pleased pleased pleased to MEET‐you, with a loud emphatic ending. This song is used on migration and to attract a female on the breeding range. Once paired, a more rambling second territorial song is given, which sounds like the Yellow Warbler’s alternate summer song. On spring migration, both species usually sing distinct songs. The two species are rarely found in the same habitat after migration when the alternate songs are more alike.

Magnolia Warbler: Common to abundant migrant from second to fourth week of May. Favours low to medium shrubs and trees, usually at eye level. Magnolias are not secretive, but they often feed behind the leaves. Listen for its short soft weeta weeta weeto or mag mag maggie song to rise at the end. Pish for it. Beware that female Magnolias are sometimes mistaken for the rare Kirtland’s Warbler. Kirtland’s wags its tail persistently whereas Magnolia does not wag its tail. A broad white basal tail band and broad black tipped tail (best seen from below) separates Magnolia in all plumages from similar species. Magnolia has a distinctive tlep call note.

Cape May Warbler: Fairly common migrant during second and third weeks of May. Breeding male is tiger‐like with its chestnut face patch and bright yellow and black stripes below. Best field mark in all plumages is yellow patch on side of the neck. Not secretive but often feeds high in trees. Song is a high thin seet seet seet seet seet on the same pitch usually given from a high perch or treetop. Prefers conifers, especially spruces even in migration; often found in Red Cedars at Point Pelee. The Cape May is one of three main warblers whose numbers increase during large outbreaks of Spruce Budworm in the boreal forest. The other two warblers whose numbers rise and fall because of budworms are the Bay‐breasted and Tennessee. See discussion on Budworm Warblers under Notes and Remarks.

Black‐throated Blue Warbler: Fairly common migrant during second and third weeks of May. Usually seen about eye level in understory of forest, but sometimes forages higher. Occasional males seen at Point Pe lee and elsewhere have extensive black spotting on the back and black streaks on crown, suggesting overshoots of the Appalachian subspecies cairnsi, but they also may be variants of the nominate subspecies caerulescens, which breeds in Ontario. Sings a slow slurred zuree zuree zuree zwee, last note higher, louder and slurred upwards. Plain female is vireo‐like, but has a very dark cheek patch and usually a diagnostic small white spot at the base of primaries. Call note is a smacking, junco‐like chip, but softer.

Yellow‐rumped Warbler: Most abundant Ontario warbler. Earliest spring warbler, with a few arriving in late March in southern Ontario, but surprisingly no more regular in late March at Point Pelee than elsewhere. Common from mid‐April to mid‐May in southern Ontario. Not a secretive warbler, it is easily seen. Prefers open woods and forest edges, usually feeding at medium heights, but also seen flycatching at the tops of trees. Some days in early May, Yellow‐rumps and Ruby‐crowned Kinglets are in every tree at Point Pelee, making the search for other species a chore. Song is a loose tinkling trill that rises or falls at the end. Learn its distinctive chep call note to identify flying birds. Taxonomy: Myrtle and Audubon’s Warblers were lumped into Yellow‐rumped Warbler by the American Ornithologists’ Union in 1973 because of interbreeding. Yellow‐rumps in Ontario are the eastern Myrtle Warbler form which has a white throat, but an occasional western Audubon’s Warbler form is seen with a bright yellow throat, more white in wingbars, different face pattern, and more white in the outermost tail feathers (hard to see). Studies show that Myrtle and Audubon’s Warblers are so closely related genetically that they are unlikely to be split back into separate species.

Black‐throated Gray Warbler: Extremely rare vagrant in Ontario from western North America. Two fall, but no spring records for Point Pelee. Be sure you see the diagnostic yellow spot in front of the eye before naming this rarity in Ontario.

Black‐throated Green Warbler: Fairly common migrant during first three weeks of May. Not secretive. Usually feeds at medium heights to high in trees. Two distinctive song types: primary song is a fast buzzy see see see see SUZ‐zie with second last note lower; alternate song is a slower buzzy zee zee zoo‐zoo zee heard more often on the breeding grounds.

Townsend’s Warbler: Extremely rare vagrant from western North America. Late April and May records for Point Pelee (4 records), Rondeau and Thickson’s Woods. ID with great caution. Taxonomy: Townsend’s and Hermit Warblers hybridize commonly. This process of gene flow is called introgression, an example of evolution in action.

Hermit Warbler: Extremely rare vagrant from western North America. One record for Point Pelee 2‐7 May 1981. This individual preferred Red Cedars. ID with great caution. Hermit or Townsend’s Warblers seen in Ontario should be checked for evidence of hybridization.

Blackburnian Warbler: Fairly common migrant during second and third weeks of May. Usually a tree top warbler, but at Point Pelee and other spring migrant traps, they often forage and sing at moderate heights on nearly leafless deciduous trees. Beginners sometimes misidentify a female Blackburnian that is high in a tree as the rare Yellow‐throated Warbler. Like many warblers, the Blackburnian has two main song types. Both songs are extremely high pitched, often not heard by those over 65 years or even younger, a sad part of getting older. A common song type is a wiry zip zip zip zip zeeeeee ending on a very high note that is diagnostic. The other song heard more on the breeding grounds after pair formation is a slower two parted lisping teetsa teetsa teetsa zizuiziri, ending on a slurred higher note.

Yellow‐throated Warbler: Very rare early southern overshoot from mid‐April to mid‐May, occasionally later. Two subspecies occur in Ontario: the white‐Iored or Sycamore subspecies albilora is the usual race seen, but watch for the coastal yellow‐lored subspecies dominica that has occurred a few times in Ontario. A slow moving warbler that creeps nuthatch‐like along branches. It usually forages and sings from high in deciduous trees or pines. The typical song of interior albilora race is a series of clear doubled whistles see‐wee, see‐wee, see‐wee, see‐wee, swee swee swee, reminiscent of a soft Indigo Bunting song. No Ontario breeding record.

Pine Warbler: Uncommon early migrant from mid‐April to early May. Except for a few late migrating first year birds, most Pines are on breeding territories by mid‐May. Even migrants are most often seen in pines when available. Pine Warblers generally creep along high horizontal branches. Often detected by its breezy short trill (3 seconds) getting louder in the middle, decreasing at the end. Sings usually from top of a pine. Chipping Sparrow’s trill is usually a longer 5 seconds. Bright adult male Pine resembles Yellow‐throated Vireo, but Pine lacks vireo’s distinct yellow eyering and has streaked sides. Yellow‐throated Vireos rarely inhabit pine trees. At the other extreme, dull female Pines often stump birders. An extremely plain warbler (often no yellow) with wingbars in May is probably a first year female Pine, voted dullest spring warbler. Watch for its creeping behaviour as a clue. An unstreaked back confirms Pine. After seeing a dull Pine Warbler in spring, you will be better prepared for those confusing fall warblers.

KirtIand’s Warbler: Endangered species in Ontario. Very rare migrant in mid‐May at Point Pelee (extremely rare vagrant north to Toronto) en route to its breeding grounds in central Michigan. Usually feeds low, preferring conifers such as Red Cedar at Point Pelee. Kirtland’s is a big warbler that habitually wags its tail. Sometimes confused with female Magnolia Warbler. Note: In the early 1900s, Kirtland’s Warblers were fairly common and probably bred on the Jack Pine plains near Petawawa in Renfrew County northeast of Algonquin Park (Harrington 1939). Speirs (1984) documented the first breeding record for Ontario in 1945 near Camp Borden in Simcoe County. This record was accepted by the Ontario Bird Records Committee (James 1984). Occasional vagrants are seen and heard in June in Jack Pine stands at Petawawa and the Bruce Peninsula.

Prairie Warbler: A rare early to mid‐May migrant. Usually forages at eye level or higher in shrub by oaks, junipers and pines. A better name would be “Scrub Warbler.” Sings a thin buzzy slurring song gradually ascending in pitch and volume, zee tee zee tee zee Zee ZEe ZEE, usually from an exposed perch or dead branch. It is often difficult to pinpoint due to its ventriloqual song.

Palm Warbler: Fairly common early migrant from mid‐April to mid‐May. Palms usually forage at eye level or near the ground in bushy fields and forest edges. Palms are not secretive. The bright yellow undertail coverts and habitual pumping of their tails make them easy to identify. Song is a buzzy trill on one tone, less emphatic than a Chipping Sparrow. Two well‐marked subspecies are easily recognizable in the field in alternate (breeding) plumage (Pittaway 1995). The commoner breeding subspecies in Ontario, the Western Palm Warbler, is yellow on the throat and undertail coverts with a distinct white belly. The eastern Yellow Palm Warbler is completely yellow below, but rare in Ontario. Yellow Palms tend to migrate earlier in spring than Western Palms; watch for them mid to late April. A few Yellow Palms may still breed in large bogs and fens east of Ottawa. Intergrades (intermediates) are uncommon.

Bay‐breasted Warbler: Fairly common about the third week of May. A rapid migrant, most of the population passes through quickly within a week. Unlike most warblers, Bay‐breasted often migrate in small pure flocks. Male is distinctive and female always shows enough bay colour for easy recognition. Spring migrants prefer tall shrubby growth at medium heights. Short high tees‐teesi‐teesi‐see song has the ringing quality of a Golden‐crowned Kinglet’s see see see call.

Black-throated Green Warbler

Female

Photo: Sam Barone

Nashville Warbler

Photo: Frank and Sandra Horvath

Nashville Warbler

Photo: Carol Horner

Golden-winged Warbler

Photo: Sam Barone

Black-and-white Warbler

Photo: Brandon Holden

Cerulean Warbler

Photo: Tim King

Pine Warbler

Photo: Sam Barone

Hooded Warbler

Female

Photo: Tom Thomas

Kentucky Warbler

Photo: Frank and Sandra Horvath

Palm Warbler

Juvenile

Photo: John Millman

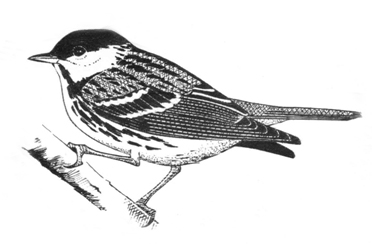

Blackpoll Warbler: Fairly common migrant, but less often seen because it arrives late after many of the leaves have grown. A few appear in mid‐May, but most migrate in late May and early June. This late migrant is usually heard singing from inside a leafed out tree at a medium height. Singing males often stay still on the same perch making them difficult to spot in dense foliage. Its distinctive song is an extremely high‐pitched staccato tsit tsit Tsit Tist Tist TSIT TSIT Tsit Tsit tsit tsit rising louder in the middle and falling off at the end.

Cerulean Warbler: Rare to uncommon migrant from early to mid‐May. Usually sings from the treetops where it is hard to spot. Song is a fast buzzy tray zray zray zreeeee with last note higher and longer. Like all tree top warblers, it will forage much lower during cold spring weather.

Black‐and‐white Warbler: Common migrant during first three weeks of May. Not secretive. Seen creeping nuthatch‐like along deciduous tree trunks and large branches at low to medium heights. Sometimes forages in dry or wet shrubbery. Learn its high‐pitched squeaky “in and out” song weet‐see weet‐see weet‐see weet‐see weet‐see weet‐see.

Male Blackpoll Warbler by Michael King.

American Redstart: Common mid to late May migrant in low and middle level shrubbery and forest edges. It flits brightly colourful wings and tail while actively flycatching. Adult males sing persistently. Songs are short and variable, high‐pitched and often switched around. Three typical songs are zee zee zee zee zee ZWEE with last note higher or tsee tsee tsee tsee‐o with last note lower or teetsy teetsy teetsy on the same level. First year males look like females, but have irregular dark spots on the head and belly. First year males sing like adult males.

Prothonotary Warbler: Endangered species in Ontario. Rare but regular throughout May at Point Pelee, Rondeau, Long Point and Hamilton. Look for it around the ponds in Tilden’s Woods at Point Pelee and along the Tulip Tree Trail near the Visitor Centre at Rondeau. Habitat is flooded woods and treed swamps. A cavity nester, it adapts well to bird boxes. Not secretive, it is active and tame, climbing on tree trunks, hopping on fallen trees, feeding at low to medium heights. It sometimes perches motionless. Listen for its clear loud tweet tweet tweet tweet tweet tweet tweet song, given from a medium to high perch. A loud dry chip call helps locate birds that are not singing. Beginners sometimes mistake the bright yellow Blue‐winged Warbler as Prothonotary, but Blue‐wing has white wingbars and black line from bill to eye.

Worm‐eating Warbler: A rare southern overshoot. A few are seen every spring at Point Pelee and elsewhere in southern Ontario. Look for it skulking on or near the ground in Tilden’s Woods at Point Pelee. It usually stays low, but sometimes is detected at medium heights when it rattles dead leaf clusters looking for insects. Males sing a rapid dry trill like a Chipping Sparrow in deciduous woods. Chipping Sparrows sing in more open habitats with scattered trees. No breeding record for Ontario.

Swainson’s Warbler: Extremely rare vagrant in southern Ontario. Two May records for Point Pelee. This secretive ground warbler should be identified with great caution.

Ovenbird: Common mid to late May migrant. A well camouflaged “hard‐to‐see” woodland ground warbler. Suggests a small thrush, but has striped instead of spotted breast. Walks on forest floor, often raising orange feathers on head. Found in drier woods and does not teeter like the waterthrushes. More often heard than seen. Distinctive “teacher” song is repeated 5‐15 times, getting increasingly louder. Sings from a medium to high perch.

Northern Waterthrush: Common migrant first three weeks of May. Secretive around woodland pools, treed swamps and thick undergrowth along slow woodland streams. Learn its loud and rapid three‐parted song twit twit twit, sweet sweet sweet, Chew Chew Chew with a distinctive ending. Often discovered by its sharp clink call note given in flight. The flight of both waterthrushes is direct, swift and low. Compared to Louisiana, the Northern is creamier yellow and more tiger‐striped below, reminiscent of a Cape May Warbler. The Louisiana is whiter and less streaked below with diagnostic tan flanks, brighter bubble gum pink legs, wider and whiter eyebrow stripe (supercilium) and larger bill. Waterthrushes walk instead of hop and teeter like Spotted Sandpipers. There is a fine behavioural difference between the two species: Northerns bob the tail, while Louisianas bob both body and tail.

Louisiana Waterthrush: Rare early migrant from second week of April to third week of May. Very secretive. Easiest to find in late April at Point Pelee around the ponds in Tilden’s Woods and the ponds along the nature trail southeast of the Visitor Centre. Both species of waterthrushes occur in the same habitat on migration. Louisianas breeding in southern Ontario prefer running woodland streams and small waterfalls. Flight is fast and direct like a Northern’s; sometimes zigzags when pairs chase each other. Distinctive song begins with three loud ringing notes followed by a sweet, jumbled warble decreasing rapidly in intensity. Also gives a sharp chink call note in flight, which is subtly different from the Northern’s. See Northern above for fine plumage distinctions.

Kentucky Warbler: A rare southern overshoot. A few are seen every spring at Point Pelee, Rondeau and elsewhere in southern Ontario. Stays near the ground, often under leafy Mayapples. Look for it in Tilden’s Woods and along the nature trails south of the Visitor Centre at Point Pelee. Song is a rapid Carolina Wren‐like torry‐ torry‐torrry‐torry; the warbler is two syllables and the wren is three syllables. No Ontario breeding records to date.

Connecticut Warbler: A rare late migrant, usually found after 20 May. Migrates when most of the leaves have grown. More often heard than seen. Song is loud repeated phrases sugar‐tweet, sugar‐tweet, sugar‐tweet. This extremely secretive warbler usually stays near the ground. Try walking slowly at an angle to a singing bird, stop and search every leaf with your binoculars. You might get lucky. I once hid inside a bush to see a singing male. Connecticut walks like an Ovenbird, unlike the hops of a Mourning Warbler.

Mourning Warbler: Late migrant with most passing through southern Ontario in late May and early June. Fairly common ground warbler, but heard more often than seen. Less secretive than the Connecticut Warbler. Sings its rolling churry churry churry chory chory, from a low perch in thickets and berry canes.

Common Yellowthroat: Common throughout May in shrubby edges of cattail marshes and wet fields with thickets, sometimes in dry shrubby and weedy areas. It often cocks its tail wren‐like. Song is a distinctive whitchity whitchity whitchity witch. Call is a husky chip note. Yellowthroats also give a rapid rattle call suggesting the song of a Worm‐eating Warbler, but it is heard in the wrong habitat for Worm‐eating. However, the yellowthroat’s rattle call is often identified as a Sedge Wren coming as it does from the appropriate habitat, but the warbler’s call is much harsher.

Chestnut-sided Warbler

Photo: Mike McEvoy

Yellow-rumped Warbler

Basic

Photo: Homer Caliwag

Yellow Warbler

Photo: Brandon Holden

Tennessee Warbler

Photo: Brandon Holden

Hooded Warbler: A rare ground warbler after mid‐April, Found in shrubby openings in mature woodlands. Population is increasing in Ontario. Migrants are seen at Point Pelee, Rondeau and north to Toronto, Presqu’ile, and Prince Edward Point near Kingston. The breeding stronghold is large woodlots near Long Point. Song suggests a very loud Magnolia Warbler, weeta weeta weete‐o, which is the key to finding a male Hooded. Also listen for its distinctive loud doonk call note. Watch for Hooded to fan and flash its diagnostic white tail feathers, the best field mark for females.

Wilson’s Warbler: A late migrant after mid‐May. Prefers moist shrubbery, particularly alders, dogwoods and willows. Song is a series of rapid chattering notes chi‐chi‐chi‐chi‐chi‐ chi‐chi‐chet‐chet dropping off at the end. Wilson’s sometimes can be detected in thick cover by its active kinglet‐like wing flicking and gnatcatcher‐like tail twitching (Pittaway 1989).

Canada Warbler: Late migrant in last two weeks of May. An uncommon ground to eye level warbler of damp scrub and understory woods. Distinctive jumbled song begins with an abrupt chip‐chupity‐swee‐ ditchety‐ditchety. Same chip used as a call note.

Painted Redstart: One specimen record for Ontario from Pickering Township in Durham Region in November 1971.

Yellow‐breasted Chat: Our largest warbler is uncommon and secretive. Regular from second week of May at Point Pelee, especially south of the DeLaurier Picnic Area. Prefers partly open dry fields with scattered trees, shrubs, thickets and vine tangles where it hides. Watch closely to see it. The chat is the spirit of the tangles, usually coming and going unseen, but not unheard. The spirit sings at night too, a weird song of varied laughs, cackles, cuks, quits, toots, whistles, mocks and harsh notes. Do not miss hearing the chat, day or night, at Point Pelee from May to July.

Male Canada Warbler by David Beadle.

Notes and RemarksTop

Songs and Calls: Most male warblers sing persistently on spring migration, long before reaching the breeding grounds. Despite their name, they do not warble, but have a variety of energetic, buzzy, lisping, trilling and musical songs. Many warblers have distinctive call notes that easily identify them. Start by learning the calls of the Yellow Warbler, Yellow‐rumped Warbler, Common Yellowthroat and Northern Waterthrush.

Budworm Warblers: Spruce Budworm (Choristoneura fumiferana) is a native moth. The larvae eat conifer needles. Large outbreaks often cover hundreds of square kilometres. The larvae provide abundant food for many birds, causing large population increases in some species. Spruce Budworm actually prefers the needles of Balsam Fir, which is the target species in many outbreaks. Widespread spraying of DDT before 1970, past cutting practices taking spruce and leaving fir, and controlling forest fires have encouraged the growth of Balsam Fir instead of spruce in the Maritime Provinces and boreal forests of Quebec and Ontario. These unnatural forest conditions have caused outbreaks of “Balsam Budworm” to be more severe than in natural forests. Populations of the three dependent budworm warblers (Cape May, Bay‐breasted and Tennessee) go up during outbreaks and go down after outbreaks. These population trends are often noticeable at migration stopovers such as Point Pelee, Rondeau and Long Point.

Pishing and Squeaking: Pishing and squeaking are two very effective techniques used to attract warblers and other passerines for close up viewing. Birds hidden in foliage will often show themselves. (1) Pishing is made by saying the word pish in a rapid series. Adding a few chits to your repertoire can vary pishing. Experienced pishers include a few Eastern Screech‐Owl whinnies and Northern Saw‐whet Owl toots for maximum effects. (2) Squeaking is making high pitched squealing sounds to attract curious birds in close. Squeaking is much harder to master than pishing. Moisten your pursed lips to make high pitched kissing and squealing sounds by sucking on the knuckles of your index and middle fingers when squeezed together. Use pishing and squeaking sparingly in heavily birded areas not to overly disturb birds and birders.

Warbler Neck: Looking up into the treetops for extended periods causes warbler neck. There are several ways to avoid neck strain: (l) use light weight binoculars with a wide soft neoprene strap; (2) see your high warbler first with the naked eye, then lift your binoculars to be in line with your eyes and the bird (try not to move your binoculars and neck at the same time); (3) stretch your arms high over your head from time to time and get regular exercise; (4) have a friend massage your neck and return the favour; (5) remember that many of the rarest warblers stay below eye level!

Warblers and Water: Woodland pools and streams are magnets for warblers. Search out wet thickets in May for hidden migrants.

Warbler Ethics: At popular birding spots, please stay on the designated birding trails. Walk slowly, stop often to observe, and speak quietly to see more birds. Allow exhausted migrant birds time to feed and rest. Use pishing, squeaking, and taped songs in moderation.

Algonquin Warblers In June: If you miss the main warbler migration in May in southern Ontario, you cannot beat Algonquin Park in June to hear and . see warblers on the breeding grounds. Along Highway 60, there are many short nature trails, each going through a different habitat for warblers. Early mornings from 7:00 to 9:00 a.m. are best before the bugs warm up to bite you. I recommend a commercial bug jacket, insect repellant and hat for maximum comfort.

Internet Migration Patterns: Check these radar maps at sunset, after sunset and frequently throughout the night for colours showing the density of birds and their passage north. Huge flocks of migrating birds are bright red.

Buffalo Nexrad covers most of western Lake Ontario and eastern Lake Erie.

Detroit Nexrad covers western Lake Erie and Point Pelee.

Cleveland Nexrad covers western Lake Erie and Point Pelee.

MacGillivray’s Warbler: One specimen record from Hamilton on 20 May 1890 was re‐evaluated by the 2010 Ontario Birds Records Committee and deleted from the Ontario checklist because of inconsistencies with the specimen. Recent investigation by several persons, including museum curators, revealed that specimen labels did not clearly indicate the specimen was collected in Hamilton, let alone in Ontario.

Chestnut-sided Warbler

Photo: Mike McEvoy

Mourning Warbler

Photo: Tom Thomas

Hooded Warbler

Female

Photo: Tom Thomas

Warbler ResourcesTop

Curson, J., D. Quinn and D. Beadle. 1994. Warblers of the Americas: An Identification Guide. Houghton Mifflin, New York. Complete descriptions of all 116 species. Superb colour plates of every species and most plumages. Detailed text. Highly recommended reference book.

Dunn, J. and K. Garrett. 1997. Warblers: A Field Guide to the Warblers of North America. Peters on Series. Houghton Mifflin Company, New York. This is the best field guide to the warblers.

Earley, C.C. 1999. Warblers of Ontario. Point Pelee Nature Series. The Friends of Point Pelee. Lithosphere Press; Guelph, Ontario. A wonderful compact guide for new and intermediate birders. Full colour photos, ID descriptions, ecological and habitat information.

Fairfield, G.M. 2001. The Ontario Spring Warbler Migration Count–2000. Analysis of daily warbler surveys in southern Ontario centred on Toronto. Graphs and interpretations of spring warbler migration. Published by the Toronto Ornithological Club.

Godfrey, W.E. 1986. The Birds of Canada. National Museums of Canada, Ottawa. The warbler illustrations by John Crosby are outstanding. Practice identifying warblers by covering the labels. Do this over and over again while repeating the field marks from memory. The Birds of Canada is a scholarly work with precise information on identification, voice, behaviour, habitat, nest and eggs, range maps and subspecies in Canada. This authoritative book should be in every birder’s library.

Harrington, P. 1939. Kirtland’s Warbler in Ontario. Jack‐Pine Warbler 17:95‐97.

Hince, T. 1999. A Birder’s Guide to Point Pelee. Published privately by author. Distributed by Wild Rose Guest House, RR 1, 21298 Harbour Road, Wheatley ON NOP 2PO. Also available at Pelee Wings Nature Store and The Friends of Point Pelee at the Visitor Centre. Essential guide to Pelee and the surrounding region. Site descriptions and maps to all the best birding areas. Annotated list of Specialty Birds. Bar graph of seasonal status for every species. Highly recommended.

James, R.D. 1984. Ontario Bird Records Committee Report for 1983. Ontario Birds 2(2):53‐65.

Lewis, H.F. 1939. Reverse Migration. Auk 56(1):13‐27.

McCracken, J.D. 1994. Golden‐winged and Blue‐winged Warblers: Their history and future in Ontario. Pages 279‐289 In Ornithology in Ontario. Edited by M.K. McNicholl and J.L.Cranmer‐Byng. Special Publication No. 1, Ontario Field Ornithologists, Toronto, and Hawk Owl Publishing, Whitby, Ontario.

Pittaway, R. 1989. Behavioural Identification of the Wilson’s Warbler. Ontario Birds 7(1):28‐29.

Pittaway, R. 1995. Recognizable Forms: Subspecies of the Palm Warbler. Ontario Birds 13(1):23‐27.

Speirs, D.H. 1984. The first breeding record of Kirtland’s Warbler in Ontario. Ontario Birds 2(2):80‐84.

Wormington, A. 1979. Second Annual Spring Migration Report‐1979. Point Pelee National Park, Leamington, Ontario. 20 pages.

Wormington, A. 1994. Notes on the status and distribution of Ontario Warblers. Unpublished Manuscript. A complete compilation on the status and distribution of Ontario warblers. Available to researchers from the author.

Kirtland's Warbler

Juvenile

Photo: Barry Cherriere

Hooded Warbler

Photo: Mark Peck

Blue-winged Warbler

Brewster's hybrid

Photo: Brandon Holden

AcknowledgementsTop

I particularly thank Ron Tozer and Alan Wormington for their invaluable assistance in the preparation of this article. For helpful comments and suggestions, I thank John Black, Bob Curry, Rob Dobos, George Fairfield, Earl Godfrey, Michel Gosselin, Tom Hince, Jean Iron, Ross James, Chris Lemieux, Kevin McLaughlin, Don Perks, Mike Runtz, Ron Scovell, Don Sutherland, Doug Tozer, Declan Troy, and Mike Turner. The warbler illustrations by David Beadle, Mike King, Peter Lorimer, Ron Scovell, and photos by Sam Barone, add greatly to the text.